International Space Station

| International Space Station | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

International Space Station insignia | ||||

| ISS Statistics | ||||

| Crew: | 3 | As of July 6 2006 | ||

| Perigee: | 352.8 km | March 5 2006 | ||

| Apogee: | 354.2 km | " | ||

| Orbital period: | 91.61 minutes | " | ||

| Inclination: | 51.64 degrees | " | ||

| Orbits per day: | 15.72 | " | ||

| Days in orbit: | 2,783 | July 4 2006 | ||

| Days occupied: | 2,070 | " | ||

| Total orbits: | 38,694 | August 28 2005 | ||

| Distance traveled: | ≈1,400,000,000 km | June 17 2005 | ||

| Average speed: | 27,685.7 km/h | " | ||

| Mass: | 183,283 kg | August 28 2005 | ||

| Width: | 73 m (across solar arrays) | June 20 2006 | ||

| Length: | 44.5 m (along core) | " | ||

| Height: | 27.5 m | " | ||

| Living volume: | 425 m³ | August 28 2005 | ||

| Air pressure: | 101.3 kPa[1] | " | ||

| International Space Station | ||||

| ||||

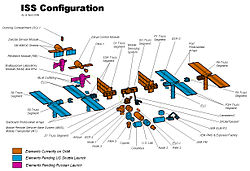

| ISS Diagram | ||||

The International Space Station (ISS) is a joint project of five space agencies: the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (United States), the Russian Federal Space Agency (Russian Federation), the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (Japan), the Canadian Space Agency (Canada) and the European Space Agency (Europe)[2].

The Brazilian Space Agency (Brazil) participates through a separate contract with NASA. The Italian Space Agency similarly has separate contracts for various activities not done in the framework of ESA's ISS works (where Italy also fully participates).

The space station is located in orbit around the Earth at an altitude of approximately 360 km (220 miles), a type of orbit usually termed low Earth orbit, whereas the actual height varies over time by several kilometres due to atmospheric drag and reboosts [3]. It orbits Earth in a period of about 92 minutes; by June 2005 it had completed more than 37,500 orbits since launch of the Zarya module on November 20 1998.

In many ways the ISS represents a merger of previously planned independent space stations: Russia's Mir 2, the U.S. Space Station Freedom and the planned European Columbus and Japanese Experiment Module.

Due to the ISS, there is a permanent human presence in space, as there have always been at least two people on board ISS since the first permanent crew entered the ISS on November 2 2000. It is serviced primarily by the Soyuz, Progress spacecraft units and Space Shuttle. The ISS is currently still under construction with a projected completion date of 2010. At present, the station has a capacity for a crew of three. Before July 6, 2006, all permanent crewmembers had come from the Russian or United States space programs. The first permanent crewmember from the European Space Agency, Thomas Reiter (German), arrived on board the ISS on 6 July 2006, to begin a 5-7 month mission as part of Discovery's STS-121 mission. [4] The ISS has however been visited by astronauts from twelve countries and was also the destination of three space tourists.

History

In the early 1980s NASA planned Space Station Freedom as a counterpart to the Soviet Salyut and Mir space stations. It never left the drawing board, and with the end of the Soviet Union and the Cold War it was cancelled. The end of the Space race prompted the U.S. administration to start negotiations with international partners, Europe, Russia, Japan and Canada in the early 1990s, in order to build a truly international space station. This project was first announced in 1993 and was called Space Station Alpha. It was planned to combine the planned space stations of all participating space agencies: NASA's Space Station Freedom, Russia's successor project to Mir, the Mir-2 and ESA's Columbus Laboratory Module that was planned to be a stand-alone spacelab.

Throughout the 1990s, construction delays hit the project, budget projections were heavily revised and the ISS structure was modified frequently. The ISS has been, as of today, far more expensive than originally anticipated. The ESA estimates the overall cost from the start of the project in the late 1980s to the prospective end in 2016 to be in the region of €100 billion.[5]

The first section, the Zarya Functional Cargo Block, was put in orbit in November 1998 on a Russian Proton rocket. Two further pieces (the Unity Module and Zvezda service module) were added before the first crew, Expedition 1, was sent. Expedition 1 docked to the ISS on November 2 2000 and consisted of U.S. astronaut William Shepherd and two Russian cosmonauts, Yuri Gidzenko and Sergei Krikalev.

ISS construction began on November 20 1998 and is now far behind the original planned schedule for completion in 2004 or 2005. This is mainly due to the halting of all NASA Shuttle flights following the Columbia disaster in early 2003 (although there had been prior delays due partly to Shuttle problems, and partly to delays stemming from the Russian space agency's budget constraints). For the two and a half years that the NASA Space Shuttle fleet was grounded, crew rotation continued on the station through the use of the Russian Soyuz spacecraft, but construction of the ISS was halted and the science conducted aboard was limited due to the crew size of two.

The reappearance of the foam debris problem on the STS-114 mission in July 2005 (the same problem that doomed Columbia) again delayed the launch sequence in 2005. As of 2006, the station is only able to accommodate three permanent crew members, compared to the expected six that the completed station will be home to.

In March 2006, a meeting of the heads of the five participating space agencies accepted the new ISS construction schedule that plans to complete the ISS by 2010. [6] A crew of six is expected to be established in 2009, after the Shuttle's next 12 construction flights following the second Return to Flight mission STS-121. Requirements for stepping up the crew size include enhanced environmental support on the ISS, a second Soyuz permanently docked on the station to function as a second 'lifeboat', more frequent Progress flights to provide double the amount of consumables, more fuel for orbit raising maneouvers, and a sufficient supply line of experimental equipment.

Building the ISS

As of the beginning of 2006 many changes have been made to the originally planned ISS, modules and other structures have been cancelled or replaced and the number of Shuttle flights to the ISS has been reduced from previously planned numbers. Still, the newest ISS Shuttle launch manifest and the current ISS design scheme reveal that more than 80% of the hardware planned to be part of the ISS in the late 90s, is still planned to be orbited to the ISS by its scheduled completion date in 2010.

Building the ISS requires more than 40 assembly and utilization flights. Of these flights, currently 33 are planned to be Space Shuttle flights, with 17 ISS-shuttle flights currently flown and 16 more planned between 2006 and 2010. Other assembly flights consist of modules lifted by the Russian Proton rocket or in the case of the Pirs Airlock by a Soyuz rocket.

In addition to the assembly and utilization flights, approximately 30 Progress spacecraft flights are required to provide logistics until 2010. Experimental equipment, fuel and consumables are and will be delivered by all vehicles visiting the ISS: the Shuttle, the Russian Progress, the European ATV (prospectively from May 2007 onwards) and the Japanese HTV.

When assembly is complete, the ISS will have a pressurized volume of approximately 1,000 cubic meters, a mass of approximately 400,000 kilograms, approximately 100 kilowatts of power output, a truss 108.4 meters long, modules 74 meters long, and a crew of six.

As of early 2006 the station consists of several modules and elements:

| Element | Flight | Launch Vehicle | Launch date | Length (m) |

Diameter (m) |

Mass (kg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zarya FGB | 1A/R | Proton rocket | 20 Nov 1998 | 12.6 | 4.1 | 19,323 |

| Unity Node 1 | 2A - STS-88 | Endeavour | 4 Dec 1998 | 5.49 | 4.57 | 11,612 |

| Zvezda Service Module | 1R | Proton rocket | 12 Jul 2000 | 13.1 | 4.15 | 19,050 |

| Z1 Truss | 3A - STS-92 | Discovery | 11 Oct 2000 | 4.9 | 4.2 | 8,755 |

| P6 Truss - Solar Array | 4A - STS-97 | Endeavour | 30 Nov 2000 | 73.2 | 10.7 | 15,900 |

| Destiny | 5A - STS-98 | Atlantis | 7 Feb 2001 | 8.53 | 4.27 | 14,515 |

| Canadarm2 | 6A - STS-100 | Endeavour | 19 Apr 2001 | 17.6 | 0.35 | 4,899 |

| Joint Airlock - Quest Airlock | 7A - STS-104 | Atlantis | 12 Jul 2001 | 5.5 | 4.0 | 6,064 |

| Docking Compartment - Pirs Airlock | 4R | Soyuz launch vehicle | 14 Aug 2001 | 4.1 | 2.6 | 3,900 |

| S0 Truss | 8A - STS-110 | Atlantis | 8 Apr 2002 | 13.4 | 4.6 | 13,970 |

| Mobile Base System for Canadarm2 | UF-2 - STS-111 | Endeavour | 5 Jun 2002 | 5.7 | 2.9 | 1,450 |

| S1 Truss | 9A - STS-112 | Atlantis | 7 Oct 2002 | 13.7 | 3.9 | 12,598 |

| P1 Truss | 11A - STS-113 | Endeavour | 24 Nov 2002 | 13.7 | 3.9 | 12,598 |

| External Stowage Platform (ESP-2) | LF1 - STS-114 | Discovery | 26 Jul 2005 | ? | ? | ? |

ISS structures and design

The ISS, when completed, will be essentially made of a set of communicating pressurized modules connected to a truss, on which are attached four large pairs of photovoltaic modules. The pressurized modules and the truss will be perpendicular: the truss spanning from starboard to port and the habitable zone extending on the aft-forward axis.

Power supply

The ISS source for electrical power is the sun: light is converted into electricity through the use of solar panels. Before assembly flight 4A (shuttle mission STS-97, November 30, 2000) the only power source were the Russian solar panels attached to the Zarya and Zvezda modules: the Russian segment of the station uses 28 volts dc (just like the Shuttle does). In the rest of the station electricity is provided by the solar panels attached to the truss at a voltage ranging from 130 to 180 volts dc, is then stabilized and distributed at 160 volts dc and transformers convert it to the user-required 124 volts dc. Power can be shared between the two segments of the station using converters, and this feature is essential since the cancellation of the Russian Science Power Platform: the Russian segment will depend on the U.S. built solar arrays for power supply.

Using a high-voltage distribution line in the so-called U.S. part of the station led to smaller power lines and thus weight savings.

Assembly

- See also: ISS assembly sequence [7]

A total of 10 main pressurized modules (Zarya, Zvezda, US Lab, Node 1, Node 2, Node 3, Columbus, Kibo, MLM and the RM) are currently scheduled to be part of the ISS by its completion date in 2010. A number of smaller pressurized sections will be adjunct to them (Soyuz spacecrafts (permanently 2 as lifeboats - 6 months rotations), Progress transporters (2 or more), the Quest and Pirs Airlocks, as well as periodically the MPLM, the ATV and the HT-V).

Pressurized modules already launched

Currently the ISS consists of only four main pressurized modules; two Russian modules Zarya and Zvezda and two US modules Destiny and Node 1. Zarya was the first module launched by a Proton rocket in November 1998, followed by a shuttle mission that connected Zarya with Node 1, the first of three node modules, 2 weeks after Zarya had been launched. This bare 2-module core of the ISS remained unmanned for the next one and a half years, until in July 2000 the Russian module Zvezda was added, allowing a minimum crew of two astronauts or cosmonauts to be on the ISS permanently.

Since 2000 the only main pressurized module delivered to the ISS was the Destiny Laboratory Module by STS-98 in 2001. The US Lab was also the first science module delivered to the ISS, whereas Zarya provides electrical power, storage, propulsion, and guidance functions and Zvezda provides living quarters, a life support system, a communication system, electrical power distribution, a data processing system, a flight control system, and a propulsion system. Node 1's primary function is to link different modules together, however fluids, environmental control and life support systems, electrical and data systems are also routed through Node 1 to supply work and living areas of the station.

Other pressurized sections of the current configuration of the ISS are the Quest Airlock and the Pirs Airlock. Soyuz spacecrafts and Progress spacecrafts docked to the ISS also extend the pressurized volume. At least one Soyuz spacecraft has to stay docked permanently as a 'lifeboat' and is replaced every six months by a new Soyuz as part of crew rotation.

Although not permanently docked with the ISS, the Multi-Purpose Logistics Module (MPLM) forms part of the ISS during Shuttle missions that include the MPLM. The MPLM is attached to Node 1 and is used for resupply and logistics flights. Speculation that the last Space Shuttle flight involving an MPLM could leave one MPLM permanently docked with the Station are fueled by the MPLM's potential capacity for a long-term stay in orbit. Modifications would need to be made, including power support and checks on whether the MPLM would influence the ISS overall structure. As of 2006, it is not planned to integrate the MPLM permanently into the ISS structure.

Pressurized modules to be launched

Node 2 - 2007

As of March, 2006, nearly all already built pressurized modules are planned to be launched by the Space Shuttle after return to flight with STS-121 in July 2006. If the current Shuttle launch sequence is not disrupted materially, Node 2 will be launched in the second quarter of 2007. Node 2 was built by the Italian Space Agency, however its ownership has been already transferred to NASA as part of a bartering agreement between NASA and ESA [8]. Node 2 will contain eight racks that provide air, electrical power, water and other systems essential to support life on the spacecraft and is scheduled to be the hub for the Columbus module and Kibo.

Columbus Laboratory Module - 2007

The next Shuttle flight after Node 2 is scheduled to bring the European module Columbus to the ISS. Columbus will be the second module mainly dedicated to science on the ISS, including the Fluid Science Laboratory (FSL), the European Physiology Modules (EPM), the Biolab, the European Drawer Rack (EDR) and various storage racks.

The Russian space agency has announced that the Multipurpose Laboratory Module (MLM) is scheduled to be launched by a Proton rocket in November 2007. The MLM is the main Russian science module, the third science module to be launched to the ISS. It will be equipped with an altitude control system that can be used as a backup by the ISS and will be docked onto the Zarya control module side docking port. The European Robotic Arm will be launched together with MLM, mated on its surface for a later deployment in space, according to a €20 million agreement signed in October 2005 between ESA and Roskosmos.

Russian Research Module - 2009

NASA's ISS schedule still includes one Russian Research Module (RM) as part of the ISS that may be docked to Zvezda and is rumoured to fly to the ISS in 2009 on a Russian Proton rocket. Construction on this module has not yet begun, which casts doubt on its actual delivery to the ISS.

Japanese Experiment Module - 2008/2009

The Japanese Experiment Module (JEM), aka KIBO is the next pressurized module on the schedule. It consists of two pressurized sections and one exposed facility. Three Shuttle flights are needed to bring KIBO into orbit; the pressurized sections are scheduled to fly in the second half of 2008 and in the first half of 2009. KIBO will be mounted on the Node 2, on the opposite side to the Columbus module.

Although it has been speculated that Node 3 has been cancelled, it is still in the new launch manifest, currently scheduled for the end of 2009. Like Node 2, Node 3 was built in Italy by the Italian Space Agency, but is owned by NASA. It will be used as a storage compartment; however its original purpose, to be a hub for the Habitation Module as well as the Crew Return Vehicle, is no longer relevant, as both items were cancelled in 2001. One of the curiosities of the ISS, the 'space window' Cupola is currently scheduled to be flown together with Node 3 on the last shuttle flight to the ISS. ESA has already finished construction and is storing the Cupola until its flight together with Node 3.

Unpressurized elements

There is also a large unpressurized truss system partially in place that will eventually support the prominent solar arrays.

Cancelled elements

- Centrifuge Accommodations Module - cancelled, would have been attached to Node 2

- Universal Docking Module - cancelled, replaced by (MLM - FGB2)

- Docking and Stowage Module - cancelled

- Habitation Module - cancelled

- Crew Return Vehicle (CRV) - cancelled

- Interim Control Module - cancelled, no need to replace Zvezda, In storage ready to launch at short notice if required.

- ISS Propulsion Module - cancelled, no need to replace Zvezda

- Science Power Platform - cancelled, power will be provided to the Russian segments partly by the US solar cell platforms

Visiting spacecraft

- Space Shuttle - resupply vehicle, assembly and logistics flights and crew rotation

- Soyuz spacecraft - crew rotation and emergency evacuation, replaced every 6 months

- Progress spacecraft - resupply vehicle

- Proposed: European (ESA) Automated Transfer Vehicle (ATV) ISS resupply spacecraft (scheduled for May 2007)

- Proposed: Japanese (JAXA) H-II Transfer Vehicle (HTV) resupply vehicle for KIBO module (scheduled for 2008)

- Proposed: Commercial cargo resupply spacecraft, under the NASA COTS (Commercial Orbital Transportation Services) program (Program ends 2010)

- Proposed: Russian Space Shuttle Kliper for possible crew rotation and as resupply transporter (scheduled for 2012)

- Proposed: Crew Exploration Vehicle possible crew rotation and as resupply transporter (officially scheduled for 2014)

- Proposed: Advanced Crew Transportation System crew rotation and resupply vehicle (possibly in 2014)

Legal aspects

Agreement

The legal structure that regulates the space station is multi-layered. The primary layer establishing obligations and rights between the ISS partners is the Space Station Intergovernmental Agreement (IGA), an international treaty signed on January 28 1998 by fifteen governments involved in the Space Station project: the United States, Canada, Japan, the Russian Federation, and eleven Member States of the European Space Agency (Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany, Italy, The Netherlands, Norway, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland and the United Kingdom). Article 1 outlines its purpose:

This Agreement is a long term international co-operative framework on the basis of genuine partnership, for the detailed design, development, operation, and utilisation of a permanently inhabited civil Space Station for peaceful purposes, in accordance with international law. [9]

The IGA sets the stage for a second layer of agreements between the partners referred to as 'Memoranda of Understanding' (MOUs), of which four exist between NASA and each of the four other partners. There are no MOUs between ESA, Roskosmos, CSA and JAXA due to the fact that NASA is the designated manager of the ISS. The MOUs are used to describe the roles and responsibilities of the partners in more detail.

A third layer consists of bartered contractual agreements or the trading of the partners' rights and duties, including the 2005 commercial framework agreement between NASA and Roskosmos that sets forth the terms and conditions under which NASA purchases seats on Soyuz crew transporters and cargo capacity on unmanned Progress transporters.

A fourth legal layer of agreements implements and supplements the four MOUs further. Notably among them is the ISS code of conduct, setting out criminal jurisdiction, anti-harassment and certain other behavior rules for ISS crewmembers. [10]

Utilization of the ISS

There is no fixed percentage of ownership for the whole space station. Rather Article 5 of the IGA sets forth that each partner shall retain jurisdiction and control over the elements it registers and over personnel in or on the Space Station who are its nationals [11]. Therefore, for each ISS module only one partner retains sole ownership. Still, the agreements to use the space station facilities are more complex.

The three planned Russian segments Zvezda, the Multipurpose Laboratory Module and the Russian Research Modules are made and owned by Russia which, as of today, also retains its current and prospective usage (Zarya, although constructed and launched by Russia, has been paid for and is officially owned by NASA). In order to use the Russian parts of the station, the partners use bilateral agreements (third and fourth layer of the above outlined legal structure). The rest of the station, (the U.S., the European and Japanese pressurized modules as well as the truss and solar panel structure and the two robotic arms) has been agreed to be utilized as follows (% refers to time that each structure may be used by each partner):

- (1) Columbus: 51% for ESA, 49% for NASA and CSA (CSA has agreed with NASA to use 2.3% of all non-Russian ISS structure)

- (2) Kibo: 51% for JAXA, 49% for NASA and CSA (2.3%)

- (3) Destiny Lab: 100% for NASA and CSA (2.3%) as well as 100% of the truss payload accommodation

- (4) Crew time and power from the solar panel structure, as well as rights to purchase supporting services (upload/download and communication services) 76.6% for NASA, 12.8% for JAXA, 8.3% for ESA and 2.3% for CSA

Costs

The most cited figure of an estimate of overall costs of the ISS is 100 billion (very often cited as USD, ESA, the only agency actually stating potential overall costs on its website estimates 100 billion EUR [12]). Giving a precise cost estimate for the ISS is however not straight forward, it is for instance hard to determine which costs should actually be contributed to the ISS program or how the Russian contribution should be measured, as the Russian space agency runs at considerably lower USD costs than the other partners.

NASA

In contrast to common belief, the overall majority of costs for NASA are not incurred for initially building the ISS modules and external structure on the ground or for construction, crew and supply flights to the ISS. In fact the Space Shuttle program, which as of 2006 nearly costs $5 billion annually, is normally not considered part of the ISS budget, although the Shuttle has been nearly solely used for ISS flights since 1998.

NASA's 2007 budget request [13] lists costs for the ISS (without Shuttle costs) as $25.6 billion for the years 1994 to 2005. For each of 2005 and 2006 about $1.7 to 1.8 billion are allocated to the ISS - this sum will be rising until 2010 when it is calculated to reach 2.3 billion and then should stay at the same level, however inflation-adjusted, until 2016, the defined end of the program.

The $1.8 billion expensed in 2005 consisted of: [14]

- Development of new hardware: Only $70 million were allocated to core development, for instance development of systems like navigation, data support or environmental.

- Spacecraft Operations: $800 million consisting of $125 million for each of software, extravehicular activity systems and logistics&maintenance. An additional $150 million is spent on flight, avionics and crew systems. The rest of $250 million goes to overall ISS management.

- Launch and Mission operations: Although the Shuttle launch costs are not considered part of the ISS budget, mission and mission integration ($300 million), medical support ($25 million) and Shuttle launch site processing ($125 million) is within the ISS budget.

- Operations Program Integration: $350 million were spent on maintaining and sustaining U.S. flight and ground hardware and software to ensure integrity of the ISS design and the continuous, safe operability.

- ISS cargo/crew: Only $140 million were spent for purchase of supplies, cargo and crew capability for Progress and Soyuz flights.

Assuming NASA's projections of average costs of $2.5 billion from 2011 to 2016 and the end of spending money on the ISS in 2017 (about $300-500 million) after shutdown in 2016, the overall ISS project costs for NASA from the announcement of the program in 1993 to its end will be about $53 billion. The 33 Shuttle flights (which, as mentioned above, are normally not considered part of the overall ISS costs) for the construction and supply of the ISS will be around $35 billion. There have also been considerable costs for designing Space Station Freedom in the 1980s and early 1990s, before the ISS program started in 1993. Therefore, although the actual costs contributed to the ISS are only half of the $100 billion figure often cited in the media, if combined with costs for the Shuttle and the design of its precursor project, it nearly reaches $100 billion for NASA alone.

ESA

ESA calculates that its contribution over the 30 year lifetime of the project will be €8 billion. The costs for the Columbus Laboratory total more than €1 billion already, costs for ATV development totals several hundred million and considering that each Ariane 5 launch costs around €125 million, each ATV launch will incur considerable costs as well.

JAXA

The Kibo Laboratory has already cost $2.8 billion according to a recent 2006 article. [15] In addition the annual running costs for Kibo will total around $350 to 400 million.

Roskosmos

A considerable part of the Russian Space Agency's budget is used for the ISS. Since 1998 there have been over two dozen Soyuz and Progress flights, the primary crew and cargo transporters since 2003. The question, how much Russia spends on the station, measured in USD, is however not easy to answer. The two modules currently in orbit are derivatives of the Mir program and therefore development costs are much lower than for other modules, in addition the exchange rate between ruble and USD is not adequately giving a real comparison to what the costs for Russia really are.

The $20 million each space tourist has paid for an available seat on a Soyuz to the ISS is only offsetting a very small part of Russia's financial contribution to the ISS.

CSA

Canada, whose main contribution to the ISS is the Canadarm2, is estimating that through the last 20 years it has contributed about $1.4 billion (Canadian $) to the ISS. [16]

Criticism of the ISS

There are many critics of the ISS, especially with regard to the biggest partner NASA. These critics view the project as a waste of both time and American tax money, inhibiting progress on more useful projects: for instance, claiming that the very often quoted estimated $100 billion USD lifetime cost could pay for dozens of unmanned scientific missions or could be used for space exploration in general or be better spent on problems on Earth.

Some critics argue that very little serious scientific research was ever convincingly planned for the ISS. They note that actual work so far has been trivial even compared to low expectations, although it has been in orbit for eight years and manned for more than five. They point out that the scientific merit of experiments conducted on the shuttle and other space stations have been negligible compared to most other funded science in space or on the ground. Other critics suppose that the ISS could accommodate important research, and believe that the cancellation of ambitious science modules, such as the Centrifuge Accommodations Module, are unwarranted. They say that the planned ISS structure meets few of the scientific objectives of the station proposed in the 1990s.

In Russia, some argue that the ISS does not principally differ from the Mir space station, uses the same general technology and cannot serve purposes that the Mir was not able to serve, so it is not a step forward.

Advocates of manned space exploration say that criticism of the ISS project is short-sighted, and that manned space research and exploration have produced billions of dollars' worth of tangible benefits to people on Earth. By some estimates, the indirect economic benefits made from commercialization of technologies developed during human space exploration have returned many times the initial investment to the economy. However, there is no consensus among economists on how to make such an estimate, since human spaceflight may or may not deserve credit for the technologies associated with it. For example, many spinoff claims concern computer technology, but it is difficult to separate NASA's needs and contributions from the vastly larger general computer industry.

Whether the ISS, as distinct from the wider space program, will be a major contributor in this sense is thus a subject of debate. Some cynical advocates have argued that even if it has no scientific value, it is still an example of international cooperation at a time of contentious international politics.

Two technical aspects of the ISS's design have been heavily criticized: (1) it requires too much maintenance, and in particular too much maintenance by risky, expensive EVAs; (2) its orbit is too highly inclined, making it difficult to reach from the Earth's surface in an economical way. The latter decision arose from the political realities of the US's desire to keep Russia involved in the program.

Present status of the ISS

After the breakup of Columbia on February 1 2003, and the subsequent two and a half year suspension of the U.S. Space Shuttle program, followed by problems with resuming flight operations in 2005, there was some uncertainty over the future of the ISS until 2006. In 2006 the international partners announced their commitment to complete the ISS by 2010.

Still the future of the ISS depends on the Space Shuttle. Due to weight restrictions and design constraints, payloads intended for the Shuttle - even if ready to fly - cannot be launched (in an economically sensible way) to the station on any other available launcher. In addition, assembly work is manpower-intensive, making it difficult to do without the assistance of EVA teams brought up by the Shuttle. Thus, if the Shuttle program suffered another disaster or a severe cut, the ISS project could probably not be continued.

Since 2003 crew exchange has been carried out using the Russian Soyuz spacecraft. Starting with Expedition 7, two-astronaut caretaker crews have been launched, instead of the previous crews of three. Because the ISS had not been visited by a shuttle for an extended period, a larger than planned amount of waste accumulated, temporarily hindering station operations in 2004. However Progress transports and the STS-114 shuttle flight took care of this problem.

The Space Shuttle Program resumed flight on July 26 2005 with the STS-114 mission of Discovery. This mission to the ISS was intended both to test new safety measures implemented since the Columbia disaster, and to deliver supplies to the station. Although the mission succeeded safely, it was not without risk; foam was shed by the external tank, leading NASA to announce future missions would be grounded until this issue was resolved.

The second Return to Flight mission, STS-121 was planned for September 2005, but Discovery's flight preparation was delayed and the mission did not launch until July 4, 2006. With the successful completion of mission STS-121, ISS assembly is scheduled to resume no earlier than August 27, 2006 with the STS-115 Space Shuttle mission.

ISS Expeditions

The International Space Station is the most-visited spacecraft in the history of space flight. As of July 12 2006, it has had 153 (non-distinct) visitors. Mir had 137 (non-distinct) visitors (See Space station). The number of distinct visitors of the ISS is 120 (see list of International Space Station visitors).

Miscellaneous

Space tourism, wedding, golf shot

As of 2006 there have been three space tourists to the ISS, each spending ca. USD 20 million; they went there aboard a Russian supply mission.

There has also been a space wedding when cosmonaut Yuri Malenchenko on the station married Ekaterina Dmitriev who was in Texas.

Golf Shot around the World is a planned event in which, on an EVA, a special golf ball, equipped with a tracking device, is hit from the station and sent into its own Low Earth orbit. The Russian space agency has consented, for a fee paid by a Canadian golf equipment manufacturer. NASA is still evaluating the risks; however, the equipment is already onboard the space station. The task was supposed to be performed on Expedition 13, but the event was postponed, and will take place at the earliest on Expedition 14.[17] [18]

Microgravity

The state of weightlessness on the ISS is popularly explained as a result of the cancelling out of the gravitational force of the Earth (that at the ISS altitude is still 88% of 1 g) by the centrifugal force produced by the ISS orbiting the planet. In a more formal physics description, the state of weightlessness is a result of the fact that the ISS is in constant free fall, which according to the equivalence principle is indiscernable from being in a state where all forces (including gravitational force) are absent. However, due to (1) the drag resulting from the residual atmosphere, (2) vibratory acceleration due to mechanical systems and the crew on board the ISS, (3) orbital corrections by the on-board gyroscopes or thrusters, and (4) the spatial separation from the real centre of mass of the ISS, the environment on the station is often described as microgravity, with a level of gravity on the order of 2-1000 millionth of g (the value varies with the frequency of the disturbance; the low value occurs at frequencies below 0.1 Hz, the higher value at frequencies of 100 Hz or more)[19]

See also

ISS-related articles

- List of International Space Station visitors

- List of ISS spacewalks performed from the ISS or visiting spacecraft

- List of manned spaceflights to the ISS for a comprehensive chronological list of all manned spacecraft that have visited the ISS, including the spacecraft's respective crews

- List of unmanned spaceflights to the ISS — Progress supply flights and unmanned automatic docking space station modules

Other

- Kliper

- Lunar space elevator

- Mir

- Progress spacecraft

- Salyut

- Skylab

- Soyuz spacecraft

- space flight simulator

- Space colonization

- Space station for statistics of occupied space stations

- Transhab

- NASA TV sometimes serves live video feeds from Station

Footnotes

- ^ International Space Station Status Report #06-7 [1]

- ^ 10 of its member states are currently participating [2]; Austria, Finland, Ireland, Portugal, and the United Kingdom chose not to participate; Greece and Luxembourg joined ESA later.

- ^ The image on the right side despicts a graph of the altitude of the ISS since launch in 1998.

- ^ rhttp://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/americas/5154396.stm

- ^ "How Much Does It Cost?". International Space Station. European Space Agency. 9 Aug 2005. Retrieved 18 Jul.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ http://www.flightglobal.com/Articles/2006/03/03/Navigation/177/205237/NASA+commits+to+Shuttle+missions+to+International+Space.html

- ^ http://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/station/structure/iss_manifest.html Official NASA assembly sequence

- ^ The Columbus module will be flown to the ISS by Shuttle in return for ESA manufacturing both Node 2 and Node 3 for NASA.

- ^ http://www.esa.int/esaHS/ESAH7O0VMOC_iss_0.html

- ^ http://portal.unesco.org/shs/en/file_download.php/785db0eec4e0cdfc43e1923624154cccFarand.pdf

- ^ http://www.esa.int/esaHS/ESAH7O0VMOC_iss_0.html

- ^ http://www.esa.int/esaHS/ESAQHA0VMOC_iss_0.html

- ^ http://www.nasa.gov/about/budget/index.html

- ^ http://www.nasa.gov/pdf/55411main_28%20ISS.pdf

- ^ http://www.belleville.com/mld/belleville/news/editorial/14204392.htm

- ^ http://www.space.gc.ca/asc/eng/iss/facts.asp

- ^ http://www.e21golf.com/]

- ^ http://www.spaceref.com/news/viewnews.html?id=1093

- ^ European Users Guide to Low Gravity Platforms, European Space Agency. Template:PDFlink

External links

- SpaceRef - Regularly updated detailed status reports of the station.

- ISS Familiarization and Training Manual - NASA July 1998 (PDF format)

- Current ISS Vital Statistics

- NASA 3D Java Tracker for ISS and other Satellites

- International Space Station — CSA Site

- International Space Station — Energia site

- International Space Station — ESA site

- International Space Station — JAXA site

- International Space Station — AEB site

- International Space Station — NASA site

- International Space Station — EuroNews report (Real player video stream)

- International Space Station from Encyclopedia Astronautica

- NASA Space Partnership Development

- NASA Commercial Orbital Transportation Services program

- Spacelink — Space Product Development

- The Planetary Society

- http://www.seds.org/pub/seds/National/misc/why-space

- Solar Transit: ISS with Discovery — The ISS with STS-114 transit the sun.

- Lunar Transit: ISS — The ISS transits the moon.

- ISS sighting:

- See the ISS from your home town— by Heavens Above

- View the ISS from your location — by NASA

- NASA Human Spaceflight - ISS Assembly Sequence webpage

- Space Station Newsgroup - sci.space.station

- Unofficial Shuttle Launch Manifest

- Track the ISS with Google Maps

- ISS Fanclub

- Detailed list of canceled components

- Boeing's Integrated Defense System: International Space Station Solar Power - Detailed information on solar arrays power supply