Female genital mutilation

| |

| Description | Partial or complete removal of the external female genitalia, or other injury to the female genital organs, for non-medical reasons[2] |

|---|---|

| Areas practised | Primarily 28 countries in sub-Saharan and north-east Africa[3] |

| Number affected | 140 million worldwide as of 2013, including 101 million in Africa[2] |

| Age performed | Typically ages 4–10; in some communities a few days after birth[4] |

Female genital mutilation (FGM), also known as female genital cutting and female circumcision, is defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as "all procedures that involve partial or total removal of the external female genitalia, or other injury to the female genital organs for non-medical reasons."[2] FGM is practised as a cultural ritual by ethnic groups in 28 countries in sub-Sarahan and north-east Africa, as well as in parts of Asia, the Middle East and within immigrant communities elsewhere.[3] It is typically carried out on girls aged four to ten, with or without anaesthesia, by a traditional circumciser using a knife, razor or scissors.[4]

The practice involves one or more of several procedures, which vary according to the ethnic group. They include removal of all or part of the clitoris and clitoral hood; removal of all or part of the clitoris and inner labia; and in its most severe form (infibulation) removal of all or part of the inner and outer labia and the fusion of the wound. In this last procedure, which the WHO calls Type III FGM, a small hole is left for the passage of urine and menstrual blood, and the wound is opened up for intercourse and childbirth.[5] The health effects depend on the procedure but can include recurrent infections, chronic pain, infertility, epidermoid cysts, complications during childbirth and fatal hemorrhaging.[6]

Around 140 million women and girls around the world have undergone FGM, including 101 million in Africa.[7] Ten percent have experienced Type III, which is predominant in Djibouti, Somalia and Sudan, and in parts of Eritrea and Ethiopia.[8] The practice is an ethnic marker, rooted in gender inequality, ideas about purity, modesty and aesthetics, and attempts to control women's sexuality by reducing their sexual desire.[9] In communities that practise it, it is supported by women and men, particularly by the women, who see it as a source of honour and authority, and an essential part of raising a daughter well.[10]

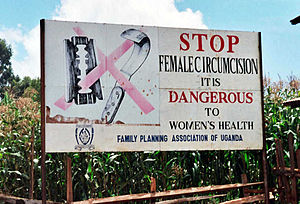

The United Nations General Assembly voted unanimously in 2012 to take all necessary steps to end FGM, with the 54 nations of the African Group introducing the text of the resolution.[11] It has been outlawed in most of the key countries in which it is practised and across the rest of the world.[12] The international opposition is not without its critics. Anthropologist Richard Shweder argues that the medical and ethical arguments of FGM eradicationists have not been scrutinized carefully enough,[13] while Sylvia Tamale, a Ugandan legal scholar, cautions that some African feminists object to what she calls the imperialist infantilization of African women inherent in the Western criticism.[14] Anthropologist Eric Silverman writes that FGM is one of the "central moral topics of contemporary anthropology," raising questions about pluralism and multiculturalism within a debate framed by colonial and post-colonial history.[15]

Terminology

The procedures were known as female circumcision (FC) until the early 1980s.[16] The term female genital mutilation came into use after the publication of The Hosken Report: Genital and Sexual Mutilation of Females (1979) by the American feminist writer Fran Hosken (1920–2006).[17] The Inter-African Committee on Traditional Practices Affecting the Health of Women and Children began referring to female genital mutilation in 1990, and the following year the WHO recommended this wording to the United Nations.[18] It has since become the dominant term within the medical literature.[19] The word mutilation differentiates FGM from male circumcision and stresses its severity.[20] The term is strongly opposed by some commentators, including Richard Shweder, who has called it a gratuitous and invidious label.[21]

Other terms in use include female genital cutting (FGC), female genital surgeries, female genital alteration, female genital excision and ethnic female genital modification.[22] USAID uses the combined term female genital mutilation/cutting (FGM/C).[23] The term infibulation (Type III FGM) derives from the Roman practice of fastening a fibula or brooch across the outer labia of female slaves.[24]

Local terms include tahara in Egypt, tahur in Sudan and bolokoli in Mali, words associated with purification.[25] In several countries all but the most severe form is known as sunna circumcision, although the term sunna wrongly implies that it is required by Islam.[26] A sunna kashfa in Sudan involves cutting off half the clitoris.[27] Another term used for procedures other than Type III is nuss (half),[28] and a procedure similar to Type III, but where the inner labia are sewn together instead of the outer labia, is known in Sudan as al juwaniya ("the inside type").[29] Type III is known as pharaonic circumcision (tahur faraowniya, or pharaonic purification) in Sudan[30] – a reference to the practice in Ancient Egypt under the Pharaohs – but Sudanese circumcision in Egypt.[31] Stanlie James writes that the procedures are described in Sudan as "going to the back of your house" and in Nigeria as "having your bath."[32]

Circumcisers, age of girls

The procedure is generally performed, with or without anaesthesia, by a traditional circumciser (a cutter or exciseuse), usually an older woman who also acts as the local midwife, known as a daya in Egypt. Male barbers, who assume the role of health workers in some areas, may also carry out FGM, as well as male cirumcision.[33] In a few countries, such as Sudan and Kenya, FGM is often performed by medical personnel.[34] When traditional circumcisers are involved, non-sterile cutting devices are likely to be used, including knives, razors, scissors, cut glass and sharpened rocks, and sutures may be made from agave or acacia thorns.[35] A nurse in Uganda, quoted in 2007 in The Lancet, said a circumciser would use one knife to cut up to 30 girls at a time.[36]

FGM is most often carried out between the ages of four and ten,[37] but the wide variation in the age the girls are cut, which includes a few days after birth, signals that FGM is not invariably used as a rite of passage between childhood and adulthood. In Egypt 90 percent are cut between five and 14 years of age; in Ethiopia, Mali and Mauritania over 60 per cent before the age of five; and a 1997 survey found that 76 percent of girls in Yemen are cut within two weeks of birth.[38]

Procedures and health effects

Overview of classification

The procedure used varies according to ethnicity.[39] The sources agree that no typology is entirely accurate, because there is considerable overlap between categories, and procedures vary according to practitioners.[40] The surveys on which the international agencies rely are based on questionnaires completed by the women themselves; to attempt to examine respondents would be financially prohibitive and might face resistance.[40] According to UNICEF women have responded using 50 different terms to describe what was done to them.[41] Difficulties arise in trying to compare these terms across cultures, and in translating them into English.[42]

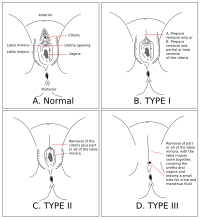

The WHO divides the main procedures into three categories, Types I–III (see image right), a classification adopted in 1996 and revised in 2008. There is a fourth category, Type IV, for miscellaneous procedures such as piercing and cauterization.[43] A 2006 study, in which 255 girls and 282 women in Sudan were examined and asked to describe their cutting, suggested that there was significant under-reporting of the severity of the procedures because the subjects were confusing the WHO's Types II and III. The study's authors advised the WHO to revise its classification.[31] UNICEF instead uses (1) cut, no flesh removed (pricking); (2) cut, some flesh removed; (3) sewn closed; and (4) type not determined/unsure/doesn't know.[44]

WHO Types I and II

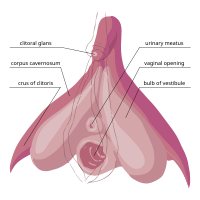

The WHO's Type I is subdivided into two. Type Ia is the removal of the clitoral hood, which is rarely, if ever, performed alone[45] More common is Type Ib (clitoridectomy), the partial or total removal of the clitoris.[46] Susan Izett and Nahid Toubia of RAINBO, in a report for the WHO, write: "the clitoris is held between the thumb and index finger, pulled out and amputated with one stroke of a sharp object. Bleeding is usually stopped by packing the wound with gauzes or other substances and applying a pressure bandage. Modern trained practitioners may insert one or two stitches around the clitoral artery to stop the bleeding."[47]

Type II (excision) is partial or total removal of the clitoris and inner labia, with or without removal of the outer labia.[48] Around 90 percent of women and girls who experience FGM undergo Types I and II, or pricking without removal of flesh (which falls within Type IV).[49]

WHO Type III

Type III (infibulation) is the removal of all external genitalia and the fusing of the wound, leaving a small hole (2–3 mm)[6] for the passage of urine and menstrual blood. The inner and outer labia are cut away, with or without excision of the clitoris.[5] A hole is created by inserting something into the wound before it closes, such as a twig or rock salt. The wound is sutured, using surgical thread, agave or acacia thorns, and the girl's legs are tied from hip to ankle for a period, perhaps 2–6 weeks, until the tissue has bonded, forming a wall of flesh and skin across the vulva.[50] Anthropologist Janice Boddy witnessed the infibulation of two sisters in northern Sudan in 1976; the procedure was carried out by a traditional circumciser, or midwife, using an anaesthetic:

A crowd of habobat (grandmothers) have gathered in the yard – not a man in sight. ... The girl lies docile on an angarib, beneath which smoulders incence in a cracked clay pot. Her hands and feet are stained with henna applied the night before. Several kinswomen support her torso; two others hold her legs apart. Miriam [the midwife] thrice injects her genitals with local anesthetic, then, in the silence of the next few moments, takes a small pair of scissors and quickly cuts away her clitoris and labia minora; the rejected tissue is caught in a bowl below the bed. ... I am surprised there is so little blood. ... Miriam staunches the flow with a white cotton cloth. She removes a surgical needle from her midwife's kit ... and threads it with suture. She sews together the girl's outer labia leaving a small opening at the vulva. After a liberal application of antiseptic the operation is over.

Women gently lift the sisters as their angaribs are spread with multicolored birishs, "red" bridal mats. The girls seem to be experiencing more shock than pain ... Amid trills of joyous ululations we adjourn to the courtyard for tea; the girls are also brought outside. There they are invested with the jirtig: ritual jewelry, perfumes, and cosmetic pastes worn to protect those whose reproductive ability is vulnerable to attack from malign spirits and the evil eye. The sisters wear bright new dresses, bridal shawls called garmosis (singular), and their family's gold. Relatives sprinkle guests with cologne, much as they would at a wedding; redolent incense rises on the morning air. Newly circumcised girls are referred to as little brides (arus); much that is done for a bride is done for them, but in a minor key. Importantly, they have now been rendered marriageable.[51]

Boddy wrote that older women in Sudan recalled a procedure much more painful, in which the circumciser would scrape away the external genitals with a straight razor, and with no anaesthetic. She would then pull the skin on either side of the wound together and secure it with acacia thorns, inserting a straw or hollow reed to create a hole for urine and menstrual blood. The girl would lie with her legs tied together for up to 40 days.[52]

The infibulated woman's vulva is cut open for sexual intercourse and childbirth. It can take up to two years for a husband to penetrate his wife's infibulation. Boddy wrote in 1989 that it was a point of pride for men in Sudan that their wives give birth within a year of marriage, so the midwife might have to be sent for secretly to enlarge the wife's opening.[53] Hanny Lightfoot-Klein, a social psychologist, interviewed 300 Sudanese women and 100 Sudanese men in the 1980s and described the penetration by the men of their wives' infibulation:

The penetration of the bride's infibulation takes anywhere from 3 or 4 days to several months. Some men are unable to penetrate their wives at all (in my study over 15%), and the task is often accomplished by a midwife under conditions of great secrecy, since this reflects negatively on the man's potency. Some who are unable to penetrate their wives manage to get them pregnant in spite of the infibulation, and the woman's vaginal passage is then cut open to allow birth to take place. ... Those men who do manage to penetrate their wives do so often, or perhaps always, with the help of the "little knife." This creates a tear which they gradually rip more and more until the opening is sufficient to admit the penis. In some women, the scar tissue is so hardened and overgrown with keloidal formations that it can only be cut with very strong surgical scissors, as is reported by doctors who relate cases where they broke scalpels in the attempt.[54]

WHO Type IV

A variety of other procedures are collectively known as Type IV, which the WHO defines as "all other harmful procedures to the female genitalia for non-medical purposes, for example, pricking, piercing, incising, scraping and cauterization." The WHO does not include cosmetic procedures such as labiaplasty or procedures used in sex reassignment surgery within its categories of FGM (see below).[55]

Type IV ranges from ritual nicking of the clitoris to stretching the labia or clitoris, burning or scarring the genitals, or introducing harmful substances into the vagina to tighten it.[56] Social scientist Stanlie M. James writes that Mairo Usman Mandara, a Nigerian surgeon, has described several practices that involve cutting internal genitalia (introcision); these include hymenotomy, the removal of a hymen regarded as too thick, practised by the Hausa in West Africa. They also include gishiri cutting, in which the vagina's anterior wall is cut with a razor blade or penknife to enlarge it; according to James, this might be done during obstructed labour or to address other medical issues.[57] Izett and Toubia write that it often results in vesicovaginal fistulae and damage to the anal sphincter.[58]

Reinfibulation and defibulation

Women may request reinfibulation – the restoration of the infibulation – after giving birth, known in Sudan as El-Adel (re-circumcision or, literally, "putting right" or "improving"). Two cuts are made around the vagina, then sutures are put in place to tighten it to the size of a pinhole. Vanja Bergrren writes that this has the effect of mimicking virginity. It may also be carried out just before marriage, after divorce or to prepare elderly women for death.[59]

Defibulation, or deinfibulation, is a surgical technique to reverse the closure of the vaginal opening after infibulation; it consists of a vertical cut opening up normal access to the vagina.[60] This may be accompanied by removal of scar tissue and labial repair. Procedures have been developed to repair clitoral integrity, such as by Pierre Foldes, a French urologist and surgeon, and Marci Bowers, an American surgeon who studied his work, using intact clitoral tissue from inside women's bodies to form a new clitoris.[61]

Complications

FGM has no known health benefits.[62] It has immediate and late complications, which depend on several factors: the type of FGM; the conditions in which the procedure took place and whether the practitioner had medical training; whether unsterilized or surgical single-use instruments were used; whether surgical thread was used instead of agave or acacia thorns; the availability of antibiotics; how small a hole was left for the passage of urine and menstrual blood; and whether the procedure was performed more than once (for example, to close an opening regarded as too wide or re-open one too small).[6]

Immediate complications include fatal hemorrhage, acute urinary retention, urinary infection, wound infection, septicemia, tetanus and transmission of hepatitis or HIV if instruments are non-sterile or reused.[6] It is not known how many girls and women die from the procedure; few records are kept, complications may not be recognized, and fatalities are rarely reported.[63]

Late complications vary depending on the type of FGM performed.[6] The formation of scars and keloids can lead to strictures, obstruction or fistula formation of the urinary and genital tracts. Urinary tract sequelae include damage to urethra and bladder with infections and incontinence. Genital tract sequelae include vaginal and pelvic infections, dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia and infertility.[35] Complete obstruction of the vagina results in hematocolpos and hematometra.[6] Other complications include epidermoid cysts that may become infected, neuroma formation, typically involving nerves that supplied the clitoris, and pelvic pain.[64]

FGM may complicate pregnancy and place women at higher risk for obstetrical problems, which are more common with the more extensive FGM procedures.[6] Thus, in women with Type III FGM who have developed vesicovaginal or rectovaginal fistulae – holes that allow urine and faeces to seep into the vagina – it is difficult to obtain clear urine samples as part of prenatal care, making the diagnosis of conditions such as preeclampsia harder.[35] Cervical evaluation during labour may be impeded and labour prolonged. Third-degree laceration, anal sphincter damage and emergency caesarean section are more common in women who have experienced FGM.[6] Neonatal mortality is also increased. The WHO estimated that an additional 10–20 babies die per 1,000 deliveries as a result of FGM; the estimate was based on a 2006 study conducted on 28,393 women attending delivery wards at 28 obstetric centers in Burkina Faso, Ghana, Kenya, Nigeria, Senegal and Sudan. In those settings all types of FGM were found to pose an increased risk of death to the baby: 15 percent higher for Type I, 32 percent for Type II and 55 percent for Type III.[65]

Psychological complications include depression and loss of trust in caregivers.[66] Toubia writes that girls living in communities where FGM is practised are torn between fear of the procedure and wanting to please their parents and gain social status. She writes that many infubulated women live with chronic anxiety and depression and fear of infertility.[46] Feelings of shame and betrayal can develop when they move outside their traditional circles and are confronted with the view that mutilation is not the norm.[6] They typically report sexual dysfunction and dyspareunia (painful sexual intercourse), but FGM does not necessarily destroy sexual desire in women. According to several studies in the 1980s and 1990s, the women said they were able to enjoy sex, though the risk of sexual dysfunction was higher with Type III.[67]

Where and why FGM occurs

Prevalence

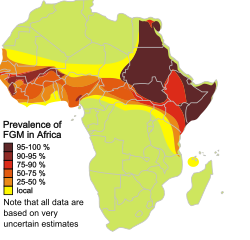

According to the WHO in 2013, 140 million women and girls around the world have experienced FGM, including 101 million girls over the age of ten in Africa.[2] The single highest number of cases is in Nigeria because of its population of 150 million;[69] as of 1993 it accounted for an estimated 30 million cases.[70]

Around 90 percent of the procedures carried out are Types I, II or pricking (Type IV), and 10 percent Type III.[49] Type III is predominant in Djibouti, Somalia and Sudan, and in areas of Eritrea and Ethiopia near those countries.[71] As of 2008 it was estimated that over five million women aged 15–49 years old were living with infibulation.[72]

A 2013 UNICEF report documented FGM in 28 African countries, with the top rates found in Somalia (98 percent of women affected), Guinea (96 percent), Djibouti (93 percent), Egypt (91 percent), Eritrea (89 percent), Mali (89 percent), Sierra Leone (88 percent), Sudan (88 percent), Gambia (76 percent), Burkina Faso (76 percent), Ethiopia (74 percent), Mauritania (69 percent), Liberia (66 percent), and Guinea-Bissau (50 percent).[3] FGM is practised by different ethnic groups within these countries, so a country's overall prevalence rate may be affected by a high rate within one group but a low rate within another.[73]

Outside Africa FGM occurs in Indonesia, Malaysia, and among ethnic minorities in Iran, Iraq, Oman and Yemen.[6] It has also been documented in Central and South America, India, Israel and the United Arab Emirates, and by anecdote in Colombia, the Congo, Oman, Peru and Sri Lanka.[74] There are immigrant communities that practise it in Australia and New Zealand, Europe, Scandinavia, the United States and Canada.[6]

In 2005 and in 2013 UNICEF reported downward trends in the practice of FGM. Fewer women in the 15–25 age group had been cut in Benin, Burkina Faso, Central African Republic, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Kenya, Nigeria, Tanzania and Yemen.[75] In Egypt and Guinea around half the women aged 15–49 years who had themselves experienced FGM said their daughters had experienced it.[76] In Kenya and Tanzania girls were three times less likely to have undergone it than their mothers, and rates in Benin, the Central African Republic, Iraq, Liberia and Nigeria had dropped by almost 50 percent.[77] The organization also reported a downward trend in the ages at which FGM is performed; their surveys suggested the median age had fallen in Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, Egypt, Kenya and Mali. Possible explanations include that, in countries clamping down on the practice, it is easier to cut a younger child without being discovered, and that the younger the girls are, the less they can resist.[75]

Reasons

The circumcision rituals are seen as a joyful celebration of community values that serve to reinforce ethnic boundaries.[79] When anthropologist Ellen Gruenbaum told a Sudanese friend, legal scholar Asma M. Abdel Halim, that the practice seemed to her to be a taboo subject, Abdel Halim replied: "It's not a secret; we celebrate it!"[80] A woman from the Kisii people in Kenya told sociologist Mary Nyangweso Wangila that the children of uncircumcised women "may die from the curse of the ancestors for disobeying tradition ... muacha mila ni mtumwa [one who abandons her culture is a slave]."[81]

FGM is viewed by its practitioners as an essential part of raising a girl.[82] Among the reasons cited are hygiene and aesthetics, purity and honour, and birth control.[83] The promotion of fertility is another reason: political scientist Gerry Mackie writes that the women's fertility is emphasized by de-emphasizing their sexuality.[84] Most often cited is a desire to promote female virginity and fidelity.[85] Female monogamy protects patrilineage by increasing the likelihood that a man is the father of his wife's children,[86] and infibulation almost guarantees monogamy because of the pain associated with sex and the difficulty of opening an infibulation without being discovered.[87] Women whose husbands travel may be reinfibulated during the man's absence. The procedure also helps to prevent rape.[88]

The primary sexual concerns vary between communities. Rahman and Toubia write that the focus in Egypt, Sudan and Somalia is on curbing premarital sex, whereas in Kenya and Uganda it is to reduce a woman's sexual desire for her husband so that he can more easily take several wives. In both cases, they argue, the aim is to serve the interests of male sexuality.[89] Anthropologist Rose Oldfield Hayes argued in 1975 that, in Sudan, virginity is more of a concept than a physiological state, and that a woman can regain her virginity and honour (her ird, or sexual dignity) by being infibulated.[90]

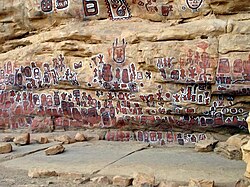

Female genitals are regarded within communities that practise FGM as dirty and ugly; physicians Miriam Martinelli and Jaume Enric Ollé-Goig write that the preference is for women's genitalia to be "flat, rigid and dry."[91] In some societies, such as among the Dogon people of Mali, the procedure is performed to differentiate between the genders, based on the belief that the clitoris confers masculinity on a girl and the foreskin of a boy makes him feminine. Gruenbaum writes that in northern Sudan the clitoris and labia (the "masculine" parts) are viewed as ugly, and the smooth, infibulated vulva as feminine, at least by women who support infibulation.[92] There are also various myths about the dangers of the clitoris: girls are told it will keep on growing, will harm a baby if it comes into contact with the baby's head, can make men impotent, and that failing to have it removed will see them shunned by the community.[93] A more practical reason for FGM's continuance is that the female circumcisers or midwives rely to some extent on the practice for their living and status, and are therefore inclined to declare it a cultural necessity.[94]

Mackie compares FGM with the practice of footbinding in China. Like FGM, footbinding was an ethnic marker carried out on young girls, was nearly universal where practised, controlled sexual access to women, was tied to ideas about honour, appropriate marriage, health, fertility and aesthetics, was supposed to enhance male sexual pleasure, and was supported by the women themselves.[95]

Support from women

In the rural Eygyptian hamlet where we have conducted fieldwork some women were not familiar with groups that did not circumcise their girls. When they learned that the female researcher was not circumcised their response was disgust mixed with joking laughter. They wondered how she could have thus gotten married and questioned how her mother could have neglected such an important part of her preparation for womanhood.

— Sandra D. Lane and Robert A. Rubinstein, 1996[96]

A 1988 poem by Somali woman Dahabo Musa described infibulation as the "three feminine sorrows": the procedure itself, the wedding night when the woman has to be cut open, then childbirth when she has to be cut again.[97] Despite the abundant literature on the suffering of women with infibulation, the women themselves commonly insist on the procedure for their daughters, or for themselves after childbirth.[98] Oldfield Hayes reported in 1975 that educated Sudanese men living in cities who refused to have their daughters infibulated – wanting to opt instead for clitoridectomy – would find the girls had been sewn up after their grandmothers arranged a supposed visit to relatives.[99]

Nearly 59 percent of 3,210 Sudanese women in physician Asma El Dareer's 1980s study said they preferred Types II and III over Type I.[100] Women in Sudan discussing circumcision with Janice Boddy in 1984 depicted Type I by opening their mouths and Type III by closing them tight, asking her: "Which is better, an ugly opening or a dignified closure?" Boddy wrote that the women avoided being photographed laughing or smiling for the same reason, preferring human orifices to be left closed or minimized, particularly female ones.[101]

Izett and Toubia write that any change to the state of a woman's infibulation can affect her sense of identity and security. They cite the case of a Somali mother of three who was advised to remain defibulated after childbirth to cure her gonorrhoea, but who insisted on being re-infibulated, leading to pain and infection so severe she could hardly walk. They argue that she did this out of "her own sense of impurity," not for her husband's benefit.[98] Women who have not undergone FGM may find themselves shunned by other women and less likely to find a husband. Sociologist Elizabeth Heger Boyle writes that, in Tanzania, the Masai will not call an uncircumcised woman "mother" when she has children, and the Kuria laugh at uncut women when they go bathing. In several communities uncut women may not be allowed to attend funerals and other public events.[102]

Some Western feminists – to the anger of their African counterparts – have attributed the women's support for FGM to false consciousness, the idea that they have simply internalized the sexism of their environments.[103] Mackie calls the support a "belief trap": "a belief that cannot be revised because the costs of testing the belief are too high." The cost of dissent in this case, he writes, is that the dissenters may fail to have descendants.[104]

Support from men

In a study in the Gambia, where Types I and II are practised and three out of 4 women are cut, just over 60 percent of men said they supported FGM and intended to have it performed on their daughters. Almost 72 percent did not know that it had negative health effects. Most said they were not involved in the decision to have their daughters cut. Men between 31 and 45 expressed the least support for it.[105]

A reason women often offer in support of infibulation is that it enhances male sexual pleasure. Gruenbaum reports that men seem to enjoy the effort to penetrate their wife's infibulation, and "can be very generous with gifts of gold or other precious things when they find the tightness of the opening to their liking."[106] Some studies have suggested otherwise.[84] Fewer than 20 percent of 1,545 men in a 1980s study by Sudanese physician Asma El Dareer said they preferred Type III over the other forms.[100]

FGM and religion

Mackie writes that FGM is found only in or adjacent to Islamic groups, but is not practised in most Muslim countries. It is also not practised in Mecca and Medina, Islam's holiest cities, where the Saudis regard it as a pagan custom. There is no mention of it in the Koran, although it is praised in several hadith, sayings attributed to Mohammed, as noble but not required.[88] Islamic scholars debate whether it is desirable, and several Muslim leaders have spoken out against it.[107] Mackie argues that, although FGM is pre-Islamic, the practice was reinforced by its intersection with Islam's codes of female modesty, honour and seclusion.[108] FGM has also been practised in Christian and animist communities too, including by the Christian Copts in Egypt and Sudan.[109] Judaism requires male circumcision, but does not allow it for girls; Shaye J. D. Cohen writes that the only Jews known to have practised FGM are the Beta Israel of Ethiopia.[110]

History and opposition

Origins in Africa

But if a man wants to know how to live, he should recite it [a magical spell] every day, after his flesh has been rubbed with the b3d [an unknown substance] of an uncircumcised girl and the flakes of skin [šnft] of an uncircumcised bald man.

— Inscription on Egyptian sarcophagus

c. 1991–1786 BCE[111]

Mackie writes that the origins of the practice are obscure.[112] There is a reference to it on the sarcophagus of Sit-hedjhotep, in the Egyptian Museum, dating back to Egypt's Middle Kingdom, c. 1991–1786 BCE (see right).[111] The Greek geographer Strabo (c. 64 BCE – c. 23 CE) wrote of it after visiting Egypt around 25 BCE: "This is one of the customs most zealously pursued by them [the Egyptians]: to raise every child that is born and to circumcise the males and excise the females."[113] The philosopher Philo of Alexandria (c. 20 BCE – 50 CE) contrasted the Egyptian practice with God's commandment in the Book of Genesis (c. 950–500 BCE) that boys be circumcised, writing: "the Egyptians by the custom of their country circumcise the marriageable youth and maid in the fourteenth (year) of their age, when the male begins to get seed, and the female to have a menstrual flow."[114]

A heiroglyph of a woman in labour and the physical examination of mummies by Australian pathologist Grafton Elliot Smith (1871–1937) suggest that Type III was not performed in ancient Egypt, although as part of the mummification process, the skin of the outer labia was pulled toward the anus to form a covering over the pudendal cleft (possibly to prevent sexual violation), which gave the appearance of Type III. Smith wrote that soft tissues were often removed by embalmers, or had simply deteriorated, so that it was not possible to determine from the mummies whether Types I and II had been practised.[115]

Egyptologist Mary Knight writes that there is only one extant reference from antiquity that suggests FGM might have been practised outside Egypt. Xanthus of Lydia wrote in a history of Lydia in the fifth century BCE: "The Lydians arrived at such a state of delicacy that they were even the first to 'castrate' their women." Knight argues from the context that "castrate" refers here to a form of sterilization.[116]

Mackie writes that FGM in Africa became tied up with the slave trade. The Egyptians took captives in the south to be used as slaves, and slaves from Sudan were exported through the Red Sea to the Persian Gulf. The English explorer William Browne (1768–1813) reported in 1799 that infibulation was carried out on slaves in Egypt to prevent pregnancy (although the Swedish ethnographer, Carl Gösta Widstrand, argued that the slave traders simply paid a higher price for women who were infibulated anyway), and the Portuguese missionary João dos Santos (d. 1622) wrote of a group in Mogadishu who had a "custome to sew up their Females, especially their slaves being young to make them unable for conception, which makes these slaves sell dearer, both for their chastitie, and for better confidence which their Masters put in them."[112] Thus, Mackie argues, patterns of slavery across Africa account for the patterns of FGM found there, and "[a] practice associated with shameful female slavery came to stand for honor."[117]

Practice in Europe and the United States

Gynaecologists in 19th-century Europe and the United States would also remove the clitoris for various reasons, including to treat masturbation, believing that the latter caused physical and mental disorders.[119] The first reported clitoridectomy in the West was carried out in 1822 by Karl Ferdinand von Graefe (1787–1840), a surgeon in Berlin, on a teenage girl regarded as an "imbecile" who was masturbating.[120]

Isaac Baker Brown (1812–1873), an English gynaecologist, president of the Medical Society of London, and co-founder of St. Mary's Hospital in London, believed that the "unnatural irritation" of the clitoris caused epilepsy, hysteria and mania, and "set to work to remove [it] whenever he had the opportunity of doing so," according to his obituary in the Medical Times and Gazette.[118] He did this several times between 1859 and 1866, sometimes with removal of the inner labia too.[121] When he published his views in a book, On the Curability of Certain Forms of Insanity, Epilepsy, Catalepsy, and Hysteria in Females (1866), doctors in London accused him of quackery, mutilation and operating without consent, and he died in poverty after being expelled from the Obstetrical Society the following year.[122]

In the United States J. Marion Sims (1813–1883), regarded as the father of gynaecology – controversially so because of his experimental surgery on slaves – followed Brown's work, and in 1862 slit the neck of a woman's uterus and amputated her clitoris, "for the relief of the nervous or hysterical condition as recommended by Baker Brown," after she complained of period pain, convulsions and bladder problems.[123] Sources differ as to when the last clitoridectomy was performed in the United States. G.J. Barker-Benfield writes that it continued until least 1904 and perhaps into the 1920s.[124] A 1985 paper in the Obstetrical & Gynecological Survey said it was performed into the 1960s to treat hysteria, erotomania and lesbianism.[125]

Colonial opposition in Kenya

Protestant missionaries in Kenya, which was a British colony from 1895 until 1963, condemned FGM as early as 1906.[126] As a result of the opposition to it, FGM became a focal point of the independence movement among the Kikuyu, the country's main ethnic group. Historians Robert Strayer and Jocelyn Murray write that uncircumcised girls in Kenya were outcasts, often ending up as prostitutes, so to ask the Kikuyu to give up FGM was to them unthinkable. There was also a fear among the Kikuyu that Europeans were campaigning against FGM so they could marry uncircumcised girls and acquire more Kenyan land.[127]

Such was the focus on FGM that the 1929–1931 period in Kenya became known in the country's historiography as the female circumcision controversy. A person's stance toward FGM became a test of loyalty, either to the Christian churches or to the Kikuyu Central Association.[126] The Church Missionary Society led the opposition,[128] and sought support from humanitarian and women's rights groups in London, where the issue was raised in the House of Commons.[126] Then as now, support for the practice came from the women themselves. E. Mary Holding, a Methodist missionary in Meru, Kenya, wrote that the ritual was an entirely female affair, organized by women's councils known as kiama gia ntonye ("the council of entering"). The circumcised girls' mothers were allowed to become members of these councils, a position of some authority, which was yet another reason to support the practice.[129]

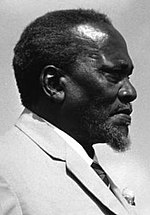

Jomo Kenyatta (c. 1894–1978) – who became Kenya's first prime minister in 1963 and had earlier studied anthropology at the London School of Economics under Bronisław Malinowski (1884–1942) – wrote that, for the Kikuyu, the institution of FGM was the "conditio sine qua non of the whole teaching of tribal law, religion and morality, and that no Kikuyu man or woman would marry someone who was not circumcised.[130] In a letter to The Guardian in or around 1930 he wrote:

The real argument lies not in the defense of the general surgical operation or its details, but in the understanding of a very important fact in the tribal psychology of the Kikuyu – namely, that this operation is still regarded as the essence of an institution which has enormous educational, social moral and religious implications, quite apart from the operation itself. For the present it is impossible for a member of the tribe to imagine an initiation without clitoridoctomy [sic]. Therefore the surgical abolition of the surgical element in this custom means to the Kikuyu the abolition of the whole institution.[131]

In 1956, under pressure from the British, the council of male elders (the Njuri Nchecke) in Meru, Kenya, announced a ban on clitoridectomy. Historian Lynn Thomas writes that over two thousand girls – mostly teenagers, but some as young as eight – were charged over the next three years with having carried out the procedure on each other with razor blades, a practice that came to be known as Ngaitana ("I will circumcise myself"), so-called because the girls claimed to have cut themselves to avoid naming their friends.[132] Thomas describes the episode as significant in the history of FGM because it made clear that its apparent victims were in fact its perpetrators.[133]

Growth of African opposition

Opposition to the colonial attitudes notwithstanding, Africans also began to campaign against FGM. In the 1920s the Egyptian Doctors' Society called for it to be banned, and in December 1928 Egyptian surgeon Ali Ibrahim Pasha, the director of Cairo University, spoke out against it during a medical conference. Opposition in Egypt continued throughout the 1930s to 1950s. A booklet published by Al Doktor in May 1951 criticized it as hazardous and unnecessary. An Egyptian women's magazine, Hawwaa, published a series of critical articles about it in 1957 and 1958, and the next year it became illegal to perform FGM in any of Egypt's state-run health facilities.[134]

Opposition gathered pace during the United Nations Decade for Women (1975–1985).[136] In 1975 Rose Oldfield Hayes published a paper in the American Ethnologist about infibulation in north Sudan, bringing the issue to wider academic attention.[137] In 1977 Egyptian physician and feminist Nawal El Saadawi, in her The Hidden Face of Eve: Women in the Arab World (translated into English in 1980), described FGM as a dangerous procedure intended to control women's sexuality.[138] It was followed by similar arguments from Sudanese physician Asma El Dareer in her Woman, Why Do You Weep? (1982).[135] In 1979 the Cairo Family Planning Association held a seminar, "Bodily Mutilation of Young Females," and a group of Egyptian legislators, physicians and others began writing pamphlets and holding meetings.[139]

In 1979 the American feminist writer Fran Hosken presented her influential The Hosken Report: Genital and Sexual Mutilation of Females to the WHO's first "Seminar on Harmful Traditional Practices Affecting the Health of Women and Children," which voted in favour of ending the practice.[140] The 1980s saw the framing of FGM as a human rights violation, rather than a health concern, which was an important step forward in the campaign against it.[140] The early focus on the health risks had served to medicalize the practice, which meant that health professionals had started to carry it out.[141] In 1984 a group of African NGOs met in Dakar, Senegal, leading to the formation of the Inter-African Committee on Traditional Practices Affecting the Health of Women and Children, which now has national branches in 28 African countries focusing on opposition to FGM.[142]

In June 1993 the UN World Conference on Human Rights passed the Vienna Declaration recognizing the rights of women and girls, and classifying FGM as a human-rights violation.[143] In July 2003 the African Union ratified the Maputo Protocol, guaranteeing certain rights for women, including in Article 5 an end to FGM.[144]

After Egypt's 1959 ban on FGM in state-run hospitals, the practice continued elsewhere in the country, and in 1995 CNN broadcast images of a ten-year-old girl undergoing the procedure in a barber's shop in Cairo.[145] As a result the government reversed its ban so that physicians could carry it out, but a domestic FGM Task Force was set up to persuade the government that medicalizing the procedure simply added physicians to the list of perpetrators.[146] The government restored the ban in 2007 after the death of 12-year-old Badour Shaker, who died of an overdose of anaesthesia during or after an FGM procedure for which her mother had paid a physician in an illegal clinic the equivalent of $9.00. The Al-Azhar Supreme Council of Islamic Research, the highest religious authority in Egypt, issued a statement that FGM had no basis in core Islamic law, and this enabled the government to outlaw it entirely.[147]

International opposition

As a result of immigration, FGM spread to Australia, Canada, Europe (particularly France and the UK, because of immigration from former colonies), New Zealand, Scandinavia and the United States.[148] Families who have immigrated from practising countries may send their daughters there to undergo FGM, ostensibly to visit a relative, or fly in circumcisers to conduct it in people's homes.[149] Sweden passed legislation in 1982, the first country to do so.[150] It is outlawed in Australia and New Zealand, across the European Union, and under section 268 of the Criminal Code of Canada.[151] Canada was the first to recognize FGM as a form of persecution when it granted refugee status in 1994 to Khadra Hassan Farah, who fled Somalia with her 10-year-old daughter to avoid the girl being subjected to it.[152] As of May 2012 there had been no prosecutions in Canada.[153]

There have been prosecutions in France, where FGM is covered by a provision of the penal code punishing acts of violence against children that result in mutilation or disability.[154] There are thought to be up to 30,000 women in France who have experienced FGM, and thousands of girls at risk.[155] Colette Gallard, a French family-planning counsellor, writes that when it was first encountered there, the initial reaction was that Westerners ought not to intervene, and it took the deaths of two girls in 1982, one of them three months old, for that attitude to change.[156] Between then and 2012 there were 40 trials, resulting in convictions against two practitioners and over 100 parents.[155]

There have been no prosecutions in the United Kingdom, where as of 2001 nearly 66,000 women were living with FGM and 21,000 girls were at risk, according to a study by the charity FORWARD.[157] The Prohibition of Female Circumcision Act 1985 outlawed the procedure domestically, and the Female Genital Mutilation Act 2003 and Prohibition of Female Genital Mutilation (Scotland) Act 2005 made it an offence to arrange to have it performed outside the UK on British citizens or permanent residents.[158] In June 2013 the British National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children launched a 24-hour national helpline (0800 028 3550) that children at risk can call.[159]

In the United States, the Centers for Disease Control estimated in 1997 that 168,000 girls living there had undergone FGM or were at risk.[160] Fauziya Kasinga, a 19-year-old woman from Togo and member of the Tchamba-Kunsuntu ethnic group, was granted asylum in 1996 after leaving an arranged marriage to escape FGM, setting a precedent in US immigration law.[161] Performing FGM on anyone under the age of 18 became illegal the following year with the Federal Prohibition of Female Genital Mutilation Act, and 17 states enacted similar legislation between 1994 and 2006.[162] The Transport for Female Genital Mutilation Act was passed in January 2013 and prohibits knowingly transporting a girl out of the country for the purpose of undergoing FGM.[163] Khalid Adem, who emigrated from Ethiopia to Atlanta, Georgia, became the first person in the US to be convicted in an FGM case; he was sentenced to ten years in 2006 for having severed his two-year-old daughter's clitoris with a pair of scissors.[164]

Since 2003 the United Nations has sponsored an annual International Day of Zero Tolerance to Female Genital Mutilation every 6 February,[165] and in December 2012 the UN General Assembly voted unanimously to condemn the practice and urged member states to take all necessary steps toward ending it.[11]

Criticism of the opposition

Challenges to the mainstream position

| Part of a series on |

| Medical and psychological anthropology |

|---|

| Social and cultural anthropology |

There have been several challenges to the prevailing discourse on FGM. Anthropologist Eric Silverman writes that the practice is one of the "central moral topics of contemporary anthropology," politically loaded with colonial and post-colonial history.[166] The international debates often rely on data gathered by anthropologists, who are criticized if they adopt a pluralist stance rather than defending human rights, while eradicationists stand accused of cultural colonialism.[167]

Ugandan law professor Sylvia Tamale argued in 2011 that the early Western opposition stemmed from a Judeo-Christian, voyeuristic judgment that African sexual culture, including not only FGM but also dry sex, polygyny and levirate marriage, consisted of primitive practices that required correction.[168] Fran Hosken's The Hosken Report: Genital and Sexual Mutilation of Females (1979), in particular, was criticized for ethnocentrism and its insistence on Western intervention.[169] Hosken was uncompromising in her language. She called FGM a "training ground for male violence," saw the women as "mentally castrated" and "participating in the destruction of their own kind," and argued that infibulation "teaches male children that the most extreme forms of torture and brutality against women and girls is their absolute right and what is expected of real men."[170]

Tamale writes that, following the report's publication, opposition to FGM became an obsession of anthropologists and women's rights activists, who "flocked to the continent with the zeal of missionaries to save African women from this barbaric practice."[171] While there is a significant body of African research that opposes FGM, she cautions that African feminists object to what she calls the "imperialist, racist and dehumanising infantilization of African women" inherent in attempts to stem it.[172] Historian Chima Korieh offers as an example of the objectification of African women the publication by 12 American newspapers in 1996 of the FGM ceremony of a 16-year-old girl in Kenya. The photographs won the 1996 Pulitzer Prize for Feature Photography, but according to Korieh the girl had not given permission for images of her naked body to be published or even taken.[173]

African-American feminists have come into conflict too over FGM: Stanlie James criticized the writer Alice Walker, who has campaigned against it, calling her "'possessed' of the pernicious notion that she can and must rescue those unfortunate women from themselves."[32]

Anthropologist Richard Shweder writes of the international consensus against FGM that the accuracy of the factual and moral claims are taken for granted to such an extent that the practice has become an "obvious counterargument to cultural pluralism." He argues that the research may not support this view, citing reviews of the literature on FGM in 1999, 2003 and 2005 by medical anthropologist and epidemiologist Carla Obermeyer.[174] Obermeyer wrote that her reviews indicated that the more serious medical complications are relatively infrequent.[175]

Shweder argues that anthropologists who specialize in gender issues in Africa have long been aware of the discrepancies between their own experiences and the global discourse on FGM. He cites a controversial lecture delivered in 1999 to the American Anthropological Association in Chicago, in which Sierra Leonan-American anthropologist Fuambai Ahmadu challenged the claims that FGM has a negative effect on women's sexuality, and that it stems from unwitting subjugation. On the contrary, Ahmadu argued, the ceremonies and procedures are an embrace of female authority. Ahmudu was herself cut as an adult in Sierra Leone as part of her initiation into the Bundu secret society.[176]

Comparison with cosmetic procedures

Obermeyer argues that FGM may be conducive to women's well-being within their communities in the same way that procedures such as breast implants, rhinoplasty and male circumcision may help people in other cultures.[177] The WHO does not include cosmetic procedures such as labiaplasty (reduction of the inner labia), vaginoplasty (tightening of the vaginal muscles) and clitoral hood reduction as examples of FGM; the group writes that some elective practices do fall within its categories, but its broad definition aims to avoid loopholes.[55] Gynaecologist Birgitta Essén and anthropologist Sara Johnsdotter argue that this is a double standard, with adult African women (for example, those seeking reinfibulation after childbirth) viewed as mutilators trapped in a primitive culture, while other women seeking cosmetic genital surgery are viewed as exercising their right to control their own bodies.[178]

Essén and Johnsdotter write that some doctors have drawn a parallel between cosmetic procedures and FGM.[179] Ronán Conroy of the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland argued in 2006 that cosmetic genital procedures are "driving the advance of female genital mutilation by promoting the fear in women that what is natural biological variation is a defect, a problem requiring the knife."[180]

Some of the legislation banning FGM would seem to cover cosmetic genital alteration. The law in Sweden, for example, bans operations "on the external female genital organs which are designed to mutilate them or produce other permanent changes in them ... regardless of whether consent ... has or has not been given."[181] Because anti-FGM laws are not used to stop cosmetic genital procedures, Essén and Johnsdotter argue that it seems the law distinguishes between Western and African female genitals, and deems only African women unfit to make their own decisions. Where FGM is banned even if consent is given, physicians may end up having to ask of prospective patients whether they appear to be victims of African patriarchy before deciding whether to offer them genital alteration.[179]

Arguing against these parallels, philosopher Martha Nussbaum writes that the key issue with FGM is that it is mostly conducted on children using physical force. She argues that the distinction between social pressure, which might reduce autonomy, and physical force is always morally and legally salient, and is arguably comparable to the distinction between seduction and rape.[182] She also argues that the literacy of women in practising countries is generally poorer than that of women in the Western world, and that this – together with a lack of political power – reduces their ability to make informed choices for themselves and their families.[183]

Notes

- Sources are listed in long form on first reference and short form thereafter.

- ^ Masinde, Andrew. "FGM: Despite the ban, the monster still rears its ugly head in Uganda", New Vision, Uganda, 5 February 2013.

- ^ a b c d "Female genital mutilation", World Health Organization, February 2013 (hereafter WHO 2013).

- ^ a b c "Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting: A statistical overview and exploration of the dynamics of change", UNICEF 2013 (hereafter UNICEF 2013), p. 2. The 28 countries in Africa and the percentage of women affected:

- Somalia (98 percent), Guinea (96 percent), Djibouti (93 percent), Egypt (91 percent), Eritrea (89 percent), Mali (89 percent), Sierra Leone (88 percent), Sudan (88 percent), Gambia (76 percent), Burkina Faso (76 percent), Ethiopia (74 percent), Mauritania (69 percent), Liberia (66 percent), Guinea-Bissau (50 percent), Chad (44 percent), Côte d'Ivoire (38 percent), Kenya (27 percent), Nigeria (27 percent), Senegal (26 percent), Central African Republic (24 percent), Yemen (23 percent), United Republic of Tanzania (15 percent), Benin (13 percent), Ghana (4 percent), Togo (4 percent), Niger (2 percent), Cameroon (1 percent), and Uganda (1 percent). Iraq (in the Middle East) is listed at 8 percent.

- For more information on UNICEF's data collection, see "Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (MICS)", UNICEF, 25 May 2012.

- ^ a b Toubia, Nahid. "Female Circumcision as a Public Health Issue", The New England Journal of Medicine, 331(11), 1994, pp. 712–716 (note: this paper uses an older classification system): "Girls are commonly circumcised between the ages of 4 and 10 years, but in some communities the procedure may be performed on infants, or it may be postponed until just before marriage or even after the birth of the first child."

- "Changing a harmful social convention: female genital cutting/mutilation", Innocenti Digest, UNICEF 2005 (hereafter UNICEF 2005), p. 7: "The large majority of girls and women are cut by a traditional practitioner, a category which includes local specialists (cutters or exciseuses), traditional birth attendants and, generally, older members of the community, usually women."

- ^ a b WHO 2008, p. 4: "Narrowing of the vaginal orifice with creation of a covering seal by cutting and appositioning the labia minora and/or the labia majora, with or without excision of the clitoris (infibulation)."

- p. 24: "When it is important to distinguish between variations in infibulations, the following subdivisions are proposed: Type IIIa, removal and apposition of the labia minora; Type IIIb, removal and apposition of the labia majora."

- For the wound being opened for intercourse and childbirth, see Elchalal, Uriel et al. "Ritualistic Female Genital Mutilation: Current Status and Future Outlook", Obstetrical & Gynecological Survey, 52(10), October 1997, pp. 643–651 (hereafter Elchalal et al 1997).

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Abdulcadira, Jasmine; Margairaz, C.; Boulvain, M; Irion, O. "Care of women with female genital mutilation/cutting", Swiss Medical Weekly, 6(14), January 2011 (review).

- ^ WHO 2013.

- ^ Yoder, Stanley P. and Khan, Shane. "Numbers of women circumcised in Africa", USAID, March 2008, p. 13.

- For the percentage of women living with Type III, see WHO 2008, p. 5, citing Yoder and Khan 2008, p. 13.

- For Djibouti, also see Martinelli, M. and Ollé-Goig, J.E. "Female genital mutilation in Djibouti", African Health Sciences, 12(4), December 2012 (hereafter Martinelli and Ollé-Goig 2012): "In 1997 the Ministry of Health [and] United Nation Fund for Population (UNFP) ... demonstrated that FGM/C was almost universal among women in Djibouti (98.8 %) and that 68 % of them had been subjected to type III mutilation."

- ^ James, Stanlie M. "Female Genital Mutilation," in Bonnie G. Smith (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopaedia of Women in World History, Oxford University Press, 2008 (pp. 259–262), p. 261: "The most frequently mentioned rationale is the need to control women, especially their sexuality."

- Nussbaum, Martha. "Judging Other Cultures: The Case of Genital Mutilation," Sex and Social Justice, Oxford University Press, 1999 (hereafter Nussbaum 1999), p. 124: "Female genital mutilation is unambiguously linked to customs of male domination."

- WHO 2008, p. 5: "In every society in which it is practised, female genital mutilation is a manifestation of gender inequality that is deeply entrenched in social, economic and political structures," and WHO 2013: "FGM is recognized internationally as a violation of the human rights of girls and women. It reflects deep-rooted inequality between the sexes, and constitutes an extreme form of discrimination against women."

- Rahman, Anika and Toubia, Nahid. Female Genital Mutilation: A Guide to Laws and Policies Worldwide, Zed Books, 2000 (hereafter Rahman and Toubia 2000), pp. 5–6: "A fundamental reason advanced for female circumcision is the need to control women's sexuality ... FC/FGM is intended to reduce women's sexual desire, thus promoting women's virginity and protecting marital fidelity, in the interest of male sexuality."

- "Harmful Traditional Practices Affecting the Health of Women and Children", Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, Fact Sheet No. 23, section 1A: "It is believed that, by mutilating the female's genital organs, her sexuality will be controlled; but above all it is to ensure a woman's virginity before marriage and chastity thereafter."

- Mackie, Gerry. "Ending Footbinding and Infibulation: A Convention Account", American Sociological Review, 61(6), December 1996, (pp. 999–1017), pp. 999–1000 (hereafter Mackie 1996): "Footbinding and infibulation correspond as follows. Both customs are nearly universal where practiced; they are persistent and are practiced even by those who oppose them. Both control sexual access to females and ensure female chastity and fidelity. Both are necessary for proper marriage and family honor. Both are believed to be sanctioned by tradition. Both are said to be ethnic markers, and distinct ethnic minorities may lack the practices. Both seem to have a past of contagious diffusion. Both are exaggerated over time and both increase with status. Both are supported and transmitted by women, are performed on girls about six to eight years old, and are generally not initiation rites. Both are believed to promote health and fertility. Both are defined as aesthetically pleasing compared with the natural alternative. Both are said to properly exaggerate the complementarity of the sexes, and both are claimed to make intercourse more pleasurable for the male."

- ^ Mackie 1996, p. 1009 (also available here).

- Also see interview with Sudanese surgeon Nahid Toubia: "By taking on this practice, which is a woman's domain, it actually empowers them. It is much more difficult to convince the women to give it up, than to convince the men" ("Changing attitudes to female circumcision", BBC News, 8 April 2002).

- ^ a b "General Assembly Strongly Condemns Widespread, Systematic Human Rights Violations", United Nations General Assembly, 20 December 2012: "[T]he Assembly adopted its first-ever text aimed at ending female genital mutilation, concluding a determined effort by African States. By its terms, the Assembly recognized that such mutilations were an irreparable, irreversible abuse of the human rights of woman and girls, and reaffirmed it as a serious threat to their health. States were urged to condemn all such practices, whether committed within or outside a medical institution, and take measures — including legislation — to prohibit female genital mutilations, and protect women and girls from that form of violence."

- "Intensifying global efforts for the elimination of female genital mutilations", United Nations General Assembly, Sixty-seventh session, Third Committee, Agenda item 28 (a), Advancement of women, 16 November 2012: "Urges States to condemn all harmful practices that affect women and girls, in particular female genital mutilations, whether committed within or outside a medical institution, and to take all necessary measures, including enacting and enforcing legislation to prohibit female genital mutilations and to protect women and girls from this form of violence, and to end impunity ..."

- Bonino, Emma. "Banning Female Genital Mutilation", The New York Times, 19 December 2012: "The U.N. resolution will be adopted by consensus, demonstrating the international community’s unified stance. The consensus is strengthened by the fact that two thirds of U.N. member states are co-sponsoring the resolution, with 67 states joining the 54 nations of the African Group, which initially introduced the text."

- ^ UNICEF 2013, p. 8: "Twenty-six countries in Africa and the Middle East have prohibited FGM/C by law or constitutional decree. Two of them – South Africa and Zambia – are not among the 29 countries where the practice is concentrated. ... Legislation prohibiting FGM/C has also been adopted in 33 countries on other continents, mostly to protect children with origins in practising countries."

- UNICEF 2013, p. 9: The African countries in which FGM is concentrated, and which have passed legislation against it (not counting laws passed during colonial rule), are as of 2013: Benin (passed 2003), Burkina Faso (1996), Central African Republic (1966, amended 1996), Chad (2003), Côte d’Ivoire (1998), Djibouti (1995, amended 2009), Egypt (2008), Eritrea (2007), Ethiopia (2004), Ghana (1965, amended 2007), Guinea (1965, amended 2000), Guinea-Bissau (2011), Kenya (2001, amended 2011), Mauritania (2005), Niger (2003), Nigeria, some states (1999–2006), Senegal (1999), Somalia (2012), Sudan, some states (2008–2009), Togo (1998), Uganda (2010), United Republic of Tanzania (1998), Yemen (2001). Outside Africa, FGM was also concentrated in Iraq's Kurdistan region, which passed legislation against it in 2011.

- ^ Shweder, Richard. "'What About Female Genital Mutilation?" And Why Understanding Culture Matters in the First Place" (hereafter Shweder 2002), in Richard A. Shweder, Martha Minow and Hazel Rose Markus (eds.), Engaging Cultural Differences: The Multicultural Challenge In Liberal Democracies, Russell Sage Foundation, 2002, p. 212. Also in Daedalus, 129(4), Fall 2000.

- ^ Tamale, Sylvia. "Researching and theorising sexualities" (hereafter Tamale 2011), in Sylvia Tamale (ed.), African Sexualities: A Reader, Fahamu/Pambazuka, 2011, pp. 19–20.

- ^ Silverman, Eric K. "Anthropology and Circumcision", Annual Review of Anthropology, 33, 2004, pp. 419–445 (hereafter Silverman 2004), pp. 427–428.

- ^ Rahman and Toubia 2000, p. x.

- ^ Johnsdotter, Sara and Essén, Birgitta. "Genitals and ethnicity: the politics of genital modifications", Reproductive Health Matters, 18(35), 2010, pp. 29–37 (hereafter Johnsdotter and Essén 2010), p. 30.

- ^ WHO 2008, p. 22: "In 1990, this term [FGM] was adopted at the third conference of the Inter-African Committee on Traditional Practices Affecting the Health of Women and Children, in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. In 1991, WHO recommended that the United Nations adopt this term. It has subsequently been widely used in United Nations documents and elsewhere and is the term employed by WHO."

- ^ Nussbaum, Martha. "Judging Other Cultures: The Case of Genital Mutilation," Sex and Social Justice, Oxford University Press, 1999 (hereafter Nussbaum 1999), p. 119: "Although discussions sometimes use the terms 'female circumcision' and 'clitoridectomy,' 'female genital mutilation' is the standard generic term for all these procedures in the medical literature."

- ^ UNICEF 2005: "The word 'mutilation' not only establishes a clear linguistic distinction with male circumcision, but also, due to its strong negative connotations, emphasizes the gravity of the act." For similar wording, see WHO 2008, p. 22.

- ^ Shweder, Richard. "When Cultures Collide: Which Rights? Whose Tradition of Values? A Critique of the Global Anti-FGM Campaign," in Christopher L. Eisgruber and András Sajó (eds.), Global Justice And the Bulwarks of Localism, Martinus Nijhoff, 2005, pp. 181–199 (hereafter Shweder 2005).

- ^ For "ethnic female genital modification," see Gallo, Pia Grassivaro; Tita Eleanora; and Viviani, Franco. "At the Roots of Ethnic Female Genital Modification," in George C. Denniston and Pia Grassivaro Gallo (eds.). Bodily Integrity and the Politics of Circumcision, Springer, 2006, pp. 49–50.

- For the rest, see Momoh, Comfort. "Female genital mutilation" (hereafter Momoh 2005), in Comfort Momoh (ed.), Female Genital Mutilation, Radcliffe Publishing, 2005, p. 6.

- ^ "Annex to USAID Policy on Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting (FGM/C): Explanation of Terminology", USAID, 2000.

- ^ Abdalla, Raqiya Haji Dualeh. Sisters in Affliction: Circumcision and Infibulation of Women in Africa, Zed Books, 1982, p. 10.

- ^ Rahman and Toubia 2000, p. 3.

- For tahara meaning cleanliness in Arabic, also see El Hadi, Amal Abd. "Female Genital Mutilation in Egypt" in Meredeth Turshen (ed.), African Women's Health, Africa World Press, 2000, p. 146.

- ^ Gruenbaum, Ellen. The Female Circumcision Controversy: An Anthropological Perspective, University of Pennsylvania Press, 2001 (hereafter Gruenbaum 2001), pp. 2–3, 63.

- ^ Zabus, Chantal. "Between Rites and Rights: Excision on Trial in African Women's Texts and Human Contexts," in Peter H. Marsden and Geoffrey V. Davis (eds.), Towards a Transcultural Future: Literature and Human Rights in a ' Post'-Colonial World, Rodopi 2004, pp. 112–113 (hereafter Zabus 2004).

- ^ Gruenbaum 2001, p. 3.

- ^ Gruenbaum 2001, p. 148.

- ^ Boddy, Janice. Civilizing Women: British Crusades in Colonial Sudan, Princeton University Press, 2007 (hereafter Boddy 2007), p. 1.

- ^ a b Elmusharaf, Susan; Elhadi, Nagla; and Almroth, Lars. "Reliability of self reported form of female genital mutilation and WHO classification: cross sectional study", British Medical Journal, 332(7559), 27 June 2006.

- ^ a b James, Stanlie M. "Listening to Other(ed) Voices: Reflections around Female Genital Cutting," in Stanlie M. James and Claire C. Robertson (eds.), Genital Cutting and Transnational Sisterhood, University of Illinois Press, 2002, p. 89.

- ^ UNICEF 2005, p. 7: "The large majority of girls and women are cut by a traditional practitioner, a category which includes local specialists (cutters or exciseuses), traditional birth attendants and, generally, older members of the community, usually women. This is true for over 80 percent of the girls who undergo the practice in Benin, Burkina Faso, Côte d'Ivoire, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Guinea, Mali, Niger, Tanzania and Yemen. In most countries, medical personnel, including doctors, nurses and certified midwives, are not widely involved in the practice.

- El Hadi, Amal Abd. "Female Genital Mutilation in Egypt" in Meredeth Turshen (ed.), African Women's Health, Africa World Press, 2000, p. 148 (writing of Egypt before the ban): "In the main dayas (female traditional birth attendants) and barbers (male traditional health workers) perform the circumcision, particularly in rural areas and popular urban areas."

- "How a local health barber gave up on FGM/C", UNICEF, June 2006.

- Gruenbaum 2001, p. 70: "In Nigeria, circumcision (clitoridectomv or partial clitoridectomy) may be done in concert with decorative scarification and tattooing by a male barber when a girl is just three or four years old ..."

- ^ UNICEF 2005, p. 7: "[I]n 2000, it was estimated that in 61 per cent of cases [in Egypt], FGM/C had been carried out by medical personnel. The share of FGM/C carried out by medical personnel has also been found to be relatively high in Sudan (36 per cent) and Kenya (34 per cent." Note: Egypt outlawed FGM in 2007.

- ^ a b c Kelly, Elizabeth, and Hillard, Paula J. Adams. "Female genital mutilation", Current Opinion in Obstetrics & Gynecology, 17(5), October 2005, pp. 490–494 (review).

- ^ Wakabi, Wairagala. "Africa battles to make female genital mutilation history", The Lancet, 369 (9567), 31 March 2007, pp. 1069–1070.

- ^ Toubia 1994.

- ^ UNICEF 2005, p. 6.

- Comfort Momoh, a midwife who specializes in treating FGM, writes that in Ethiopia the Falashas perform it at a few days old, the Amhara on the eighth day after birth, and the Adere and Oromo between four years and puberty; see Momoh 2005, p. 2.

- ^ UNICEF 2013, p. 46.

- ^ a b Obermeyer, Carla. "Female Genital Surgeries: The Known, the Unknown and the Unknowable", Medical Anthropology Quarterly, 31(1), 1999, pp. 79–106 (hereafter Obermeyer 1999), p. 82; also available here).

- ^ UNICEF 2013, p. 48.

- ^ Obermeyer 1999, p. 84 (also here).

- ^ "Eliminating Female Genital Mutilation", World Health Organization, 2008 (hereafter WHO 2008), pp. 4, 22–28.

- See p. 4, and Annex 2, p. 24, for the classification into Types I–IV.

- Annex 2, pp. 23–28, for a more detailed discussion.

- For an overview, see WHO 2013.

- ^ UNICEF 2013, p. 48: "In the most recent MICS and DHS, types of FGM/C are classified into four main categories: 1) cut, no flesh removed, 2) cut, some flesh removed, 3) sewn closed, and 4) type not determined/not sure/doesn't know. These categories do not fully match the WHO typology. Cut, no flesh removed describes a practice known as nicking or pricking, which currently is categorized as Type IV. Cut, some flesh removed corresponds to Type I (clitoridectomy) and Type II (excision) combined. And sewn closed corresponds to Type III, infibulation."

- ^ WHO 2008, p. 24.

- Toubia 1994: "In my extensive clinical experience as a physician in Sudan, and after a careful review of the literature of the past 15 years, I have not found a single case of female circumcision in which only the skin surrounding the clitoris is removed, without damage to the clitoris itself."

- ^ a b Toubia 1994, pp. 712–716 (this paper proposes a classification system that differs from the one used by the WHO.)

- ^ Izett and Toubia, "Female Genital Mutilation: An Overview", World Health Organization, 1998.

- WHO 2013: "1. Clitoridectomy: partial or total removal of the clitoris (a small, sensitive and erectile part of the female genitals) and, in very rare cases, only the prepuce (the fold of skin surrounding the clitoris)."

- Also see WHO 2008, p. 4: "partial or total removal of the clitoris (clitoridectomy) and/or the clitoral hood."

- ^

WHO 2008, p. 4: "Partial or total removal of the clitoris and the labia minora, with or without excision of the labia majora (excision)".

- p. 24: "When it is important to distinguish between the major variations that have been documented, the following subdivisions are proposed: Type IIa, removal of the labia minora only; Type IIb, partial or total removal of the clitoris and the labia minora; Type IIc, partial or total removal of the clitoris, the labia minora and the labia majora. Note also that, in French, the term "excision" is often used as a general term covering all types of female genital mutilation."

- ^ a b WHO 2008, p. 5, citing Yoder, Stanley P. and Khan, Shane. "Numbers of women circumcised in Africa", USAID, March 2008, p. 13ff.

- ^ Elchalal et al 1997.

- Rymer, Janice and Momoh, Comfort. "Managing the reality of FGM in the UK," in Momoh op cit, p. 22: "Twigs or rock salt may be inserted into the vagina to maintain a small opening to allow urine and menstrual fluid to pass through and the whole area may be covered with soil and bark at the end of the procedure to promote healing."

- Sharif, Khadijah F. "Female Genital Mutilation," in Nadine Taub, Beth Anne Wolfson, and Carla M. Palumbo (eds.). The Law of Sex Discrimination, Cengage Learning, 2010, p. 440: "The girl's legs are bound together at the ankle, above the knees, and around the thighs for approximately fifteen to forty days to limit movement and to facilitate proper healing. To ensure tightness of the hole, a thorn is inserted into the vagina, so that when the tissue heals, only this opening remains."

- For a 1977 study and description of Type III, see Pieters, Guy and Lowenfels, Albert B. "Infibulation in the Horn of Africa", New York State Journal of Medicine, 77(6), April 1977, pp. 729–731.

- For another description of Type III from the 1970s, see Gollaher, David. "Female Circumcision," Circumcision: A History of the World's Most Controversial Surgery, Basic Books, 2000 (pp. 187–207; hereafter Gollaher 2000), p. 191: A French doctor, Jacques Lantier, who attended an FGM procedure in Somalia in the 1970s, described how the inner and outer labia were separated and attached to each thigh using large thorns. "With her kitchen knife the woman then pierces and slices open the hood of the clitoris and then begins to cut it out. While another woman wipes off the blood with a rag, the operator digs with her fingernail a hole the length of the clitoris to detach and pull out that organ. The little girl screams in extreme pain, but no one pays the slightest attention."

After removing the clitoris with the knife, the woman "lifts up the skin that is left with her thumb and index finger to remove the remaining flesh. She then digs a deep hole amidst the gushing blood. The neighbor women who take part in the operation then plunge their fingers into the bloody hole to verify that every remnant of the clitoris is removed." See Lantier, Jacques. La Cité Magique et Magie En Afrique Noire, Libraire Fayard, 1972.

- Momoh 2005, pp. 6–7, also describes an infibulation: "[E]lderly women, relatives and friends secure the girl in the lithotomy position. A deep incision is made rapidly on either side from the root of the clitoris to the fourchette, and a single cut of the razor excises the clitoris and both the labia majora and labia minora.

"Bleeding is profuse, but is usually controlled by the application of various poultices, the threading of the edges of the skin with thorns, or clasping them between the edges of a split cane. A piece of twig is inserted between the edges of the skin to ensure a patent foramen for urinary and menstrual flow. The lower limbs are then bound together for 2–6 weeks to promote haemostatis and encourage union of the two sides ... Healing takes place by primary intention, and, as a result, the introitus is obliterated by a drum of skin extending across the orifice except for a small hole. Circumstances at the time may vary; the girl may struggle ferociously, in which case the incisions may become uncontrolled and haphazard. The girl may be pinned down so firmly that bones may fracture."

- ^ Boddy, Janice. Wombs and Alien Spirits: Women, Men, and the Zar Cult in Northern Sudan, University of Wisconsin Press, 1989 (hereafter Boddy 1989), p. 50.

- ^ Boddy 1989, p. 51.

- ^ Boddy 1989, p. 54.

- ^ Lightfoot-Klein, Hanny. "The Sexual Experience and Marital Adjustment of Genitally Circumcised and Infibulated Females in The Sudan", The Journal of Sex Research, 26(3), 1989, pp. 375–392 (also available here).

- Also see Lightfoot-Klein, Hanny. Prisoners of Ritual: An Odyssey Into Female Genital Circumcision in Africa, Routledge, 1989.

- ^ a b WHO 2008, p. 28: "Some practices, such as genital cosmetic surgery and hymen repair, which are legally accepted in many countries and not generally considered to constitute female genital mutilation, actually fall under the definition used here. It has been considered important, however, to maintain a broad definition of female genital mutilation in order to avoid loopholes that might allow the practice to continue."

- ^ WHO 2008, p. 24.

- ^ James, Stanlie M. "Female Genital Mutilation," in Bonnie G. Smith (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopaedia of Women in World History, Oxford University Press, 2008 (pp. 259–262), p. 259.

- ^ Izett and Toubia (WHO), 1998.

- ^ Bergrren, Vanja, et al. "Being Victims or Beneficiaries? Perspectives on Female Genital Cutting and Reinfibulation in Sudan", African Journal of Reproductive Health, 10(2), August 2006.

- Also see Bergrren, Vanja et al. "An explorative study of Sudanese midwives’ motives, perceptions and experiences of re-infibulation after birth", Midwifery, 20(4), December 2004, pp. 299–311.

- Serour G.I. "The issue of reinfibulation", International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstretrics, 109(2), May 2010, pp. 93–96.

- ^ Nour, N.M.; Michaels, K.B.; and Bryant, A.E. "Defibulation to Treat Female Genital Cutting: Effect on Symptoms and Sexual Function", Obstetrics & Gynecology, 108(1), July 2006, pp. 55–60.

- ^ Conant, Eve. "The Kindest Cut", Newsweek, 27 October 2009.

- Foldes, Pierre. "Surgical Repair of the Clitoris after Ritual Genital Mutilation: Results of 453 Cases", WAS Visual, accessed 17 September 2011.

- ^ Berga, Rigmor C. and Denisona Eva. "A Tradition in Transition: Factors Perpetuating and Hindering the Continuance of Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting (FGM/C) Summarized in a Systematic Review", Health Care for Women International, 34(10), 2013: "According to leading health organizations, there are no known health benefits to FGM/C ..."