Golden Dawn (Greece): Difference between revisions

| [pending revision] | [pending revision] |

Undid revision 492234396 by 75.165.165.181 (talk) Note ref "Extremismus in Griechenland". Do not edit war. |

Uastyrdzhi (talk | contribs) Dolescum: If the organization refutes the label then we can't use it even if academic sources can be found which describe Golden Dawn as Neo-Nazi, to do so would run against NPOV standards. Please refer to the ideology sections in talk. |

||

| Line 21: | Line 21: | ||

|membership_year = |

|membership_year = |

||

|membership = |

|membership = |

||

|ideology = [[Ultranationalism]]<ref>{{Citation |first=Emmanouil |last=Tsatsanis |title=Hellenism under siege: the national-populist logic of antiglobalization rhetoric in Greece |journal=Journal of Political Ideologies |volume=16 |issue=1 |year=2011 |pages=11–31 |doi=10.1080/13569317.2011.540939}}</ref><ref>{{Citation |first=Elisabeth |last=Ivarsflaten |title=Reputational Shields: Why Most Anti-Immigrant Parties Failed in Western Europe, 1980-2005 |publisher=Nuffield College, University of Oxford |year=2006 |page=15}}</ref><br>[[Metaxism]]{{Citation needed|date=May 2012}}<br>[[Authoritarianism]]<ref name="IosHist"/> |

|||

|ideology = [[Neo-Nazism]]<ref>http://www.observer.com/2012/05/socialist-francois-hollande-wins-french-presidency-neo-nazi-golden-dawn-party-advances-in-greece/</ref><ref>http://www.radioaustralianews.net.au/stories/201205/3496841.htm?desktop</ref><ref>http://edition.cnn.com/2012/05/08/world/europe/europe-far-right-austerity/index.html?eref=rss_latest</ref><ref>http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/europe/nikos-michaloliakos-the-farright-firebrand-who-holds-europes-future-in-his-hands-7720682.html</ref><ref>http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2012/may/07/neo-nazi-golden-dawn-party-greece</ref><ref>http://articles.businessinsider.com/2012-05-06/news/31592754_1_nazis-greek-election-exit-polls-show</ref><br>[[Neofascism]]<ref>http://www.aljazeerah.info/News/2012/May/10%20n/Greek%20Socialist%20Venizelos%20Launches%20Talks%20to%20Form%20Coalition%20But%20May%20Lead%20to%20Another%20Election.htm</ref><ref name="extremismreport">{{cite journal |doi=10.1007/978-3-531-92746-6_9 |year=2011 |first1=Lazaros |last1=Miliopoulos |title=Extremismus in Griechenland |journal=Extremismus in den EU-Staaten |page=154}}<br>{{Citation |first=Peter |last=Chalk |title=Non-Military Security in the Wider Middle East |journal=Studies in Conflict & Terrorism |volume=26 |issue=3 |year=2003 |pages=197–214 |doi=10.1080/10576100390211428}}<br>{{Citation |first=Moses |last=Altsech |title=Anti-Semitism in Greece: Embedded in Society |journal=Post-Holocaust and Anti-Semitism |number=23 |month=August |year=2004 |page=12}}</ref><ref name="antisem">{{Citation |first1=Dina |last1=Porat |first2=Roni |last2=Stauber |title=Antisemitism Worldwide 2000/1 |publisher=University of Nebraska Press |year=2002 |page=123}}</ref><br>[[Ultranationalism]]<ref>{{Citation |first=Emmanouil |last=Tsatsanis |title=Hellenism under siege: the national-populist logic of antiglobalization rhetoric in Greece |journal=Journal of Political Ideologies |volume=16 |issue=1 |year=2011 |pages=11–31 |doi=10.1080/13569317.2011.540939}}</ref><ref>{{Citation |first=Elisabeth |last=Ivarsflaten |title=Reputational Shields: Why Most Anti-Immigrant Parties Failed in Western Europe, 1980-2005 |publisher=Nuffield College, University of Oxford |year=2006 |page=15}}</ref><br>[[Racism]]<ref>{{Citation |first=Nicholas |last=Sitaropoulos |title=Equal treatment between persons irrespective of racial or ethnic origin: the transposition in Greece of EU Directive 2000/43 |journal=The International Journal of Human Rights |volume=8 |issue=2 |year=2004 |pages=123–158 |doi=10.1080/1364298042000240834}}</ref><br>Right-wing [[extremism]]<ref>{{Citation |first=Maria |last=Repoussi |title=Battles over the national past of Greeks: The Greek History Textbook Controversy 2006-2007 |journal=Geschichte für heute. Zeitschrift für historisch-politische Bildung |issue=1 |year=2009 |page=5}}</ref><ref>{{Citation |first=Thomas |last=Grumke |title=The transatlantic dimension of right-wing extremism |journal=Human Rights Review |volume=4 |issue=4 |year=2003 |pages=56–72 |doi=10.1007/s12142-003-1021-x}}</ref><br>[[Metaxism]]{{Citation needed|date=May 2012}}<br>[[Authoritarianism]]<ref name="IosHist"/> |

|||

|position = [[Far-right politics|Far-right]] |

|position = [[Far-right politics|Far-right]] |

||

|european = [[European National Front]] |

|european = [[European National Front]] |

||

Revision as of 18:35, 12 May 2012

Golden Dawn Χρυσή Αυγή | |

|---|---|

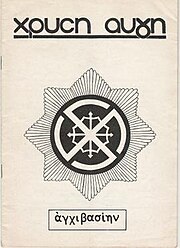

| File:Golden Dawn logo.jpg | |

| Leader | Nikolaos Michaloliakos |

| Founded | 1 November 1993 |

| Headquarters | Athens, Greece |

| Newspaper | Chrysi Augi |

| Youth wing | Youth Front |

| Ideology | Ultranationalism[1][2] Metaxism[citation needed] Authoritarianism[3] |

| Political position | Far-right |

| European affiliation | European National Front |

| Colors | Red, black |

| Greek Parliament | 21 / 300 |

| European Parliament | 0 / 22 |

| Regional units | 0 / 1,662 |

| Municipalities | 1 / 12,978 |

| Party flag | |

| |

| Website | |

| Official website | |

Golden Dawn (Greek: Χρυσή Αυγή, Chrysi Avgi, Greek pronunciation: [xriˈsi avˈʝi]) is a far-right Greek political organization led by Nikolaos Michaloliakos. It expresses anti-immigration views and its members are often accused of violent attacks on illegal immigrants. It expresses sympathy with the regime of Ioannis Metaxas. It is also commonly described as neo-Nazi[4][5] and fascist[6] although the group rejects these labels.

Golden Dawn describes itself as a "People's Nationalist Movement" and "uncompromising Nationalists."[7] Michaloliakos described Golden Dawn as opposing the "so-called Enlightenment" and the Industrial Revolution.[7][3] Religiously, they currently support both Hellenism and the Greek Orthodox Church.[8] The charter also puts the leader in total control of the party, and formalizes the use of the Roman salute for party members.[3]

Michaloliakos began the foundations of what would become Golden Dawn in 1980. It first received widespread attention in 1991, and in 1993 was registered as a political party. It temporarily ceased political operations in 2005, and was absorbed by the Patriotic Alliance. The Alliance in turn ceased operations after Michaloliakos withdrew support. In March 2007, Golden Dawn held its sixth congress, where Party officials announced the resumption of their political activism. At local elections on November 7, 2010 Golden Dawn got 5.3 per cent of the vote in the municipality of Athens, winning a seat at the City Council. In some neighbourhoods with big immigrant communities it even reached 20 per cent.[9] In the Greek legislative election, 2012, it achieved seven per cent of the popular vote, enough to enter the Hellenic Parliament for the first time. The seven per cent of the vote that Golden Dawn won on the national elections of 6 May 2012 gave the party 21 seats in the Greek Parliament.[10]

History

In December 1980, Nikolaos Michaloliakos, and a group of his supporters launched Chrysi Avgi magazine. Michaloliakos (a mathematician and a dishonourably discharged former commando reservist officer) had been active in far right politics for many years, and he had been arrested several times for politically motivated offences, such as beating attacks and illegal possession of explosive materials, which led to his discharge from the military.[3][11][12] While he was in prison, Michaloliakos met the leaders of the Greek military junta of 1967–1974, and he laid the foundations of the Hrisi Avgi party.[11] The characteristics of the magazine and the organisation were clearly National Socialist.[3] Chrysi Avgi magazine stopped being published in April 1984, when Michaloliakos joined the National Political Union and took over the leadership of its youth section.[11] In January 1985, he broke away from the National Political Union and founded the Popular National Movement – Chrysi Avgi, which was officially recognised as a political party in 1993.[11]

Golden Dawn remained largely on the margins of far right politics until the Macedonia naming dispute in 1991 and 1992.[3] The Greek newspaper Eleftherotypia reported that on October 10, 1992, about thirty Golden Dawn members attacked left-wing students at the Athens University of Economics and Business during a massive demonstration against the use of the name Macedonia by the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia.[13] Around the same time, the first far right street gangs appeared under the leadership of Giannis Giannopoulos, a former military officer who was involved with the South African Afrikaner Weerstandsbeweging (AWB) during the 1980s.[3] After the events of 1991 and 1992, Golden Dawn had gained a stable membership of more than 200 members, and Giannopoulos rose within the party hierarchy.[3] Golden Dawn ran in the 1994 European Parliament election, gaining 7.264 votes nationwide; 0.11 per cent of the votes cast.[14]

In the 1980s, the party embraced Hellenic Neopagan beliefs, writing in praise of the Twelve Olympians and describing Marxism and liberalism as "the ideological carriers of Judeo-Christianity."[15][16] Later, however, the party underwent ideological changes, also welcoming Greek Orthodox Christianity.[17]

A few Golden Dawn members participated in the Bosnian War in the Greek Volunteer Guard (GVG), which was part of the Drina Corps of the Army of Republika Srpska. A few GVG volunteers were present in Srebrenica during the Srebrenica massacre, and they raised a Greek flag at a ruined church after the fall of the town.[18] Spiros Tzanopoulos, a GVG sergeant who took part in the attack against Srebrenica, said many of the Greek volunteers participated in the war because they were members of Golden Dawn.[19] Golden Dawn members in the GVG were decorated by Radovan Karadžić, but — according to former Golden Dawn member Charis Kousoumvris — those who were decorated later left the party.[19]

In April 1996, Giannopoulos represented the party at a pan-European convention of nationalist parties in Moscow, where he presented a bust of Alexander the Great to Liberal Democratic Party of Russia leader Vladimir Zhirinovsky for his birthday.[3] Golden Dawn participated in the 1996 legislative election in September, receiving 4,487 votes nationwide; 0.07 per cent of the votes cast.[20] In October 1997, Giannopoulos published an article in Chrysi Avgi magazine calling for nationalist vigilantism against immigrants and left wingers.[21] In 1998, a prominent party member, Antonios Androutsopoulos, assaulted left wing student activist Dimitris Kousouris. The resulting media attention, along with internal party conflicts (due to poor results in the 1996 elections), led some of its most extreme members (such as Giannopoulos) to gradually fade from official party affairs.[3]

Golden Dawn continued to hold rallies and marches, and it ran in the 1999 European Parliament election in an alliance with the Front Line party, gaining 48,532 votes nationwide; 0.75 per cent of the votes cast.[3][22] Eleftherotypia criticicized Chrysi Avgi in 2005 after party members distributed homophobic fliers during an Athens gay pride parade.[23]

2005 and later

According to Golden Dawn's leader, Nikolaos Michaloliakos, the party paused its own autonomous political activities after December 1, 2005, due to clashes with extreme leftists/communists.[24] Golden Dawn members had been instructed to continue their activism within the Patriotic Alliance party, which was very closely linked to Golden Dawn.[25][26] The former leader of Patriotic Alliance, Dimitrios Zaphiropoulos, was once a member of Golden Dawn's political council, and Michaloliakos became a leading member of Patriotic Alliance.[11] Extreme leftist/communist groups had accused the Patriotic Alliance of simply being the new name of Golden Dawn.[27] Activities by Patriotic Alliance's members were often attributed to Golden Dawn (even by themselves), creating confusion.[26] This is the main reason Golden Dawn's members announced the withdrawal of their support of the Patriotic Alliance, which eventually led to the interruption of Golden Dawn's political activities.[28][29] In March 2007, Golden Dawn held its sixth congress and announced the continuation of their political and ideological activism.[30]

In 2010 Golden Dawn won 5.3 per cent of the vote in Athens. In June 2011, Foreign Policy reported that in the midst of the 2010–2011 Greek protests, gangs of Golden Dawn members are increasingly being seen in some of the higher-crime areas of Athens.[31]

In the Greek Parliament elections in 2012, the party got 6.97% of the popular vote; the parliamentary seats are still not vacated, following the normal proceedings, since there still is no resulting government.[32]

Shortly after the elections, WordPress shut down Golden Dawn's official website and blog due to violation of their Terms and Conditions.[33]

Activities

Golden Dawn claimed to have local organisations in 32 Greek cities, as well as in Cyprus.[34]

The party created the Epitropi Ethnikis Mnimis (Committee of National Memory), to organise demonstrations commemorating the anniversaries of certain Greek national events. Since 1996, Epitropi Ethnikis Mninis organizes an annual march usually on January 31 in Athens, in memory of three Greek officers who died during the Imia military crisis. According to the European National Front website, the 2006 march was attended by 2,500 people, although no neutral sources have confirmed that number. Epitropi Ethnikis Mninis has continued its activities, and the January 31 March took place in January 2010.[35][36][third-party source needed]

Epitropi Ethnikis Mnimis has organized annual rallies on June 17 in Thessalonica, in memory of Alexander the Great.[37] Police confronted the 2006 rally participants, forcing Golden Dawn and Patriotic Alliance members to leave the area after conflicts with leftist groups.[37][38] Later that day, Golden Dawn members gathered in the building of state-owned television channel ERT3 and held a protest as they tried to stop the channel from broadcasting.[38] Police surrounded the building and arrested 48 Hrisi Avgi members.[37][38]

In September 2005, Golden Dawn attempted to organise a festival called "Eurofest 2005 – Nationalist Summer Camp" at the grounds of a Greek summer camp. The planned festival depended on the participation of the German National Democratic Party of Germany, the Italian Forza Nuova and the Romanian Noua Dreaptă, as well as Spanish and American far-right groups. The festival was banned by the government.[39][40]

In June 2007, Golden Dawn sent representatives to protest the G8 convention in Germany, together with the National Democratic Party of Germany and other European far-right organisations.[41]

In May 2009, Golden Dawn took part in the European Elections receiving 23,564 votes corresponding to 0.46 per cent of the total votes.[42]

Youth Front

Golden Dawn's Youth Front has distributed fliers with nationalist messages in Athens schools and organised white power concerts. It publishes the white nationalist magazine Resistance Hellas-Antepithesi, which promotes National Socialism to young people through articles related to music and sports. The magazine is a sister publication of the United States-based National Alliance's Resistance magazine.[43][third-party source needed] The collaboration between Greek nationalists and American racialists began in 2001, after National Alliance founder William Luther Pierce visited Thessalonica, Greece. Pierce's successor, Erich Gliebe, ratified the collaboration after Pierce's death.

Political representation

In 2010, the party won its first municipal council seat[44] and entered parliament for the first time in 2012 at the cost of LAOS.

Violence by and against Golden Dawn

Members of Golden Dawn have been accused of carrying out acts of violence and hate crimes against illegal immigrants, political opponents and ethnic minorities.[45] Golden Dawn's offices have been attacked many times by anarchists and leftists. [40][46] Clashes between members of Golden Dawn and leftists have not been unusual.[47]

In January 1998, Alexis Kalofolias, vocalist of the band The Last Drive, was attacked and suffered permanent damage to his right eye, losing two per cent of his eyesight.[45][48] KLIK magazine and left wing newspaper Eleftherotypia reported that members of Golden Dawn were responsible for the attack.[45][48]

In 2000, unknown suspects vandalized the Monastirioton synagogue, a memorial for Holocaust victims and Jewish cemeteries in Thessaloniki and Athens.[49] There were claims that Hrisi Avgi's symbols were present at all four sites.[49] The KIS, the Central Board of Jewish Communities in Greece, the Coalition of the Left, of Movements and Ecology, the Greek Helsinki Monitor and others issued statements condemning these acts.[50][51] The Cyprus chapter of Hrisi Avgi has been accused of attacks against Turkish Cypriots, and one member was arrested for attacking Turkish-Cypriots in 2005.[52]

In November 2005, Golden Dawn's offices were attacked by a group of Anarchists with molotov cocktails and stones. There were gunshots, and two people (who testified that they were just passing by) were injured.[46] According to Golden Dawn, three suspects were arrested and set free.[40] During the subsequent police investigation, molotov cocktails left overs were discovered in Golden Dawn's offices.[46] Golden Dawn has stated that this was the reason for the organisation's disbandment.[24][25]

Football hooliganism

On October 6, 1999, during a football match between the Greek and Albanian national teams in Athens, Albanian supporters burnt a Greek flag in the stadium's stand. This act was captured and broadcast extensively by the Greek media that day and for many days after. That led to a series of angry reactions by Greek nationalists against foreign immigrants. In a specific case, on the night of October 22, Pantelis Kazakos, a nationalist and a member of the Golden Dawn[53][54][55], feeling as he stated: "insulted by the burning of the Greek flag", shot nine people in the center of Athens. The result of his attack was two people killed, and seven others wounded, of whom four remained paralysed for the rest of their lives. All were immigrants. Other Golden Dawn members, feeling also "insulted by the burning of the Greek flag", formed the hooligan firm Galazia Stratia (Greek for "Blue Army") the same month (October 2000). It has described itself as a "fan club of the Greek national teams" and its goal as "to defend Greek national pride inside the stadiums." It has been reported that following Golden Dawn's official disbandment in 2005, many former party members have put most of their energy into promoting Galazia Stratia.[56] Galazia Stratia is closely linked to Golden Dawn, and the two groups shared the same street address.[57] Golden Dawn made no attempt to deny the connections, openly praising the actions of Galazia Stratia in its newspaper, and accepting praise in return from the firm.[58]

Galazia Stratia and Golden Dawn have been accused of various acts of sports-related violence.[57] In September 2004, after a football match between Greece and Albania in Tirana (in which Greece lost 2–1), Albanian immigrants living in Greece went out on the streets of Athens and other cities celebrating their victory, Greek hooligans felt provoked by this and violence erupted against Albanian immigrants in various parts of Greece, resulting in one murdered Albanian in Zakynthos and many other Albanians injured. Golden Dawn and Galazia Stratia were proven to be directly responsible for many of the attacks. According to Eleftherotypia, Galazia Stratia members severely beat a Palestinian and a Bangladeshi during celebrations following the success of the Greek national basketball team at the 2006 FIBA World Championship.[56]

Periandros case

Antonios Androutsopoulos (aka Periandros), a prominent member of Golden Dawn, was a fugitive from 1998 to September 14, 2005 after being accused of the June 16, 1998 attempted murder of three left-wing students — including Dimitris Kousouris, who was badly injured.[59][60][61] Androutsopoulos had been sentenced in absentia to four years of prison for illegal weapon possession while the attempted murder charges against him were still standing.[62]

The authorities' failure to apprehend Androutsopoulos for seven years raised criticisms by the Greek media. A Ta Nea article claimed that Periandros remained in Greece and evaded arrest due to connections with the police.[59] In a 2004 interview, Michalis Chrisochoidis, the former minister of public order of PASOK, claimed that such accusations were unfounded, and he blamed the inefficiency of the Greek police. Some allege that Androutsopoulos had evaded arrest because he had been residing in Venezuela until he turned himself in 2005.[63] His trial began on September 20, 2006, and he was convicted to 21 years in prison on September 25, 2006.[64][65] Hrisi Avgi members were present in his trial, shouting nationalist slogans, and he reportedly hailed them using the Nazi salute.[64]

Imia 2008

On February 2, 2008, Golden Dawn planned to hold the annual march for the twelfth anniversary of the Imia military crisis. Anti-fascist groups organised a protest in order to cancel the march, as a response to racist attacks supposedly caused by Golden Dawn members. Golden Dawn members occupied the square in which the march was to take place, and when anti-fascists showed up, clashes occurred. During the riots that followed, Golden Dawn members were seen attacking the anti-fascists with riot police doing nothing to stop them and actually letting them pass through their lines. This led to two people being wounded by knife and another two wounded by rocks. There were allegations that Chrysi Avgi members even carried police equipment with them and that Golden Dawn's equipment was carried inside a police van.[66][67]

Athens office bombing

On March 19, 2010, a bomb described by the police as of "moderate power," was detonated in the fifth floor office of Golden Dawn, in downtown Athens. Twenty-five minutes prior to the blast, an unidentified caller contacted a local newspaper in order to announce the attack, thus leading to the evacuation of the targeted building and the surrounding area. The explosion caused substantial damage to property, but did not inflict casualties. The office was reopened on April 10, 2010.[68]

Allegations of connections to the Greek Police

In a 1998 interview with the newspaper Eleftherotypia, Georgios Romaios (the then Panhellenic Socialist Movement (PASOK) Minister for Public Order) alleged the existence of "fascist elements in the Greek police", and vowed to suppress them.[69] In a TV interview that same year, Romaios again claimed that there was a pro-fascist group within the police force although he said it was not organized, and was only involved in isolated incidents.[70] The same year, Eleftherotypia published a lengthy article called "The lower limbs of the police", which outlined connections between the police and neo-fascism.[71] Dimitris Reppas, the PASOK government spokesman, strongly denied such connections. However, the article quoted a speech by PASOK Member of Parliament Paraskevas Paraskevopoulos about a riot caused by right wing extremists, in which he said:

"In Thessaloniki it is widely discussed that far-right organisations are active in the security forces. Members of such organisations were the planners and chief executioners of the riot and nobody was arrested. A Special Forces officer, speaking at a briefing of Special Forces policemen that were to be on duty that day, told the policemen not to arrest anyone because the rioters were not enemies and threatened that should this be overlooked there would be penalties."[70]

Before the surrender of Androutsopoulos, an article by the newspaper Ta Nea claimed that the Golden Dawn had close relationships with some parts of the Greek police force.[59] In relation to the Periandros case, the article quoted an unidentified police officer who said that "half the force wanted Periandros arrested and the other half didn't". The article claimed that there was a confidential internal police investigation which concluded that:

- Golden Dawn had very good relations and contacts with officers of the force, on and off duty, as well as with common policemen.

- The police provided the group with batons and radio communications equipment during mass demonstrations, mainly during celebrations of the Athens Polytechnic uprising and during rallies by left-wing and anarchist groups, in order to provoke riots.

- The connections of the group with the force, as well as connections with Periandros, largely delayed his arrest.

- The brother of "Periandros", also a member of Golden Dawn, was a security escort of an unnamed New Democracy MP.

- Many Golden Dawn members were illegally carrying various kinds of weapons.

The newspaper published a photograph of a typewritten paragraph with no identifiable insignia as evidence of the secret investigation.[72] In the article, the Minister for Public Order, Michalis Chrysochoidis, responded that he did not recollect such a probe. Chrysochoidis also denied accusations that far right connections within the police force delayed the arrest of Periandros. He said that leftist groups, including the ultra-left anti-state resistance group 17 November, responsible for several murders, had similarly evaded the police for decades. In both cases, he attributed the failures to "stupidity and incompetence" on behalf of the force.[59]

Golden Dawn stated that rumours about the organisation having connections to the Greek police and the government are untrue, and that the police had intervened in Golden Dawn's rallies and had arrested members of the Party several times while the New Democracy party was in power (for example, during a rally in Thessaloniki in June 2006, and at a rally for the anniversary of the Greek genocide, in Athens, also in 2006).[40] Also, on January 2, 2005, anti-fascist and leftist groups invaded Golden Dawn's headquarters in Thesaloniki, under heavy police surveillance. Although riot police units were near the entrance of the building alongside the intruders, they allegedly did not attempt to stop their actions.[73][74]

In more recent years, anti-fascist and left-wing groups have claimed that many of Golden Dawn's members have close relations (and/or collaborating) with the Greek Central Intelligence Agency (KYP), and also accused the party's general-secretary Nikolaos Michaloliakos of working for the KYP from the 80s. The evidence for this is an allegedly fake[75] public document - a payslip - showing the names of both Michaloliakos and far right author and intellectual Konstantinos Plevris as operating for the agency.[76]

Allegations of Nazism

The party is regularly described as Neo-Nazi by the international news media,[78] and members may be responsible for anti-semitic graffiti.[79]

Officially denying that it has any connection to Neo-Nazism, the party maintains that it cleaves closer to the Greek fascist Ioannis Metaxas. Its so-called Nazi salute is, according to the founder of the group, "the salute of the national youth organisation of Ioannis Metaxas".[77] Its logo is likewise not a Nazi symbol but a traditional Greek meander instead.[80]

Footnotes

- ^ Tsatsanis, Emmanouil (2011), "Hellenism under siege: the national-populist logic of antiglobalization rhetoric in Greece", Journal of Political Ideologies, 16 (1): 11–31, doi:10.1080/13569317.2011.540939

- ^ Ivarsflaten, Elisabeth (2006), Reputational Shields: Why Most Anti-Immigrant Parties Failed in Western Europe, 1980-2005, Nuffield College, University of Oxford, p. 15

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Γράφει ο IΟΣ Eleftherotypia 2/07/1998 (in Greek)

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

antisemwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^

- Explosion at Greek neo-Nazi office, CNN, 19 March 2010, retrieved 2 February 2012

- "Greek minister warns of neo-Nazi political threat", B92, 31 March 2012

- "Ακροδεξιά απειλή για τη Δημοκρατία (Right-wing threat to Democracy)", Ethnos, 31 March 2012

- "Migration woes take centre stage ahead of Greek election", The Sun Daily, 4 April 2012

- "Greek Voters Punish 2 Main Parties for Economic Collapse", The New York Times, 6 May 2012

- ^

- Smith (16 December 2011), "Rise of the Greek far right raises fears of further turmoil", The Guardian

{{citation}}: Text "Helena" ignored (help) - Kravva, Vasiliki (2003), "The Construction of Otherness in Modern Greece", The Ethics of Anthropology: Debates and dilemmas, Routledge, p. 169

- Smith (16 December 2011), "Rise of the Greek far right raises fears of further turmoil", The Guardian

- ^ a b 2006 interview of Michaloliakos published in Elevtheros Kosmos newspaper.

- ^ Απάντηση στο άρθρο διαμαρτυρίας της Χρυσής Αυγής, 30th April 2012. Arguments of the Pagan group "Hellenic Church" about the Golden Dawn's positions over nationalism.

- ^ Kitsantonis, Niki. (2010-12-01) Attacks on Immigrants on the Rise in Greece. Nytimes.com. Retrieved on 2011-06-27.

- ^ Transclusion error: {{En}} is only for use in File namespace. Use {{lang-en}} or {{in lang|en}} instead. Rob Cooper "Rise of the Greek neo-Nazis: Ultra-right party Golden Dawn wants to force immigrants into work camps and plant landmines along Turkish border" Daily Mail (2012-05-07 ).

- ^ a b c d e Το κλούβιο «αβγό του φι διού» (The rotten "egg of the snake") To Vima 11/9/2005 Cite error: The named reference "Vima" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Article about Michaloliakos published on Golden Dawn's website.

- ^ ΣΧΕΣΕΙΣ ΑΚΡΟΔΕΞΙΑΣ-ΕΛ.ΑΣ. Eleftherotypia. 27/9/1998 (in Greek)

- ^ Article published in "NIGMA" magazine about Golden Dawn. (in Greek)

- ^ Our Ideology: God Religion (Η Ιδεολογία Μας: Θεός-θρησκεία), Golden Dawn's newspaper, issue 57, October 1990

- ^ Nikos Chasapopoulos (4 August 2012), "Οι φύρερ της διπλανής πόρτας", Step

- ^ Η ΝΕΑ ΑΚΡΟΔΕΞΙΑ. Eleftherotypia 18/6/2000 (in Greek)

- ^ Michas, Takis;"Unholy Alliance", Texas A&M University Press: Eastern European Studies (College Station, Tex.) pp. 22 [1]

- ^ a b Για τη Λευκή Φυλή και την Ορθοδοξία Eleftherotypia 16/07/2005 (in Greek)

- ^ Results of the 1996 legislative election.

- ^ 1998 article in Eleftherotypia.

- ^ "Ta alla Kommata", Macedonian Press Agency information on the 1999 elections.

- ^ 27/06/2005 article in Eleftherotypia [dead link]

- ^ a b Αναστέλλεται η λειτουργία της ακροδεξιάς οργάνωσης «Χρυσή Αυγή» www.in.gr. 01/12/05 (in Greek)

- ^ a b Golden Dawn stops their activities, European National Front website Cite error: The named reference "ENF_disbandment" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b Article in the website of Patriotic Alliance, stating that "those who contributed mostly in our political campaign were the youth of Golden Dawn".

- ^ Article in Eleftherotypia.

- ^ Golden Dawn announces the withdrawal of their support to Patriotic Alliance.

- ^ News of the disbandment of Patriotic Alliance, in Independent Media Center.

- ^ 12.05.07 Michaloliakos' speech during the congress. (in Greek)

- ^ KAKISSIS, JOANNA. "Fear Dimitra". Foreign Policy. Retrieved 1 September 2011.

- ^ "Greek Parliament Elections 2012". Greek Ministry of Internal Affairs.

- ^ "WordPress shuts down Golden Dawn website". New Europe (newspaper).

- ^ 11/5/2002 article in newspaper Ta Nea, about Chrysi Avgi's activities. (in Greek) [dead link]

- ^ ENF gathers in Athens from the European National Front website.

- ^ Report of the 2007 march. Xrushaugh.org (2010-02-26). Retrieved on 2011-06-27.

- ^ a b c 48 Greek nationalists arrested from the European National Front website Cite error: The named reference "48arrested" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b c Σε 48ωρη κινητοποίηση καλούν ΓΣΕΕ και ΑΔΕΔΥ Thessalia 18/6/06 (in Greek)

- ^ Ανησυχία στην Αθήνα για τις παράλληλες εκδηλώσεις ακροδεξιών και αριστερών οργανώσεων in.gr 22/12/06 (in Greek)

- ^ a b c d Golden Dawn press release (in Greek)

- ^ [2] Golden Dawn’s anti globalisation attendance against G8 convention in Germany (in Greek)

- ^ European Elections 2009. Ekloges-prev.singularlogic.eu. Retrieved on 2011-06-27.

- ^ The Growth of White Power Music. Natall.com (2006-03-04). Retrieved on 2011-06-27.

- ^ http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2012-04-29/fascist-salutes-return-to-greece-as-anti-immigrants-chase-voters.html

- ^ a b c Eleftherotypia's article about attacks by Golden Dawn. (in Greek)

- ^ a b c Επεισόδια με πυροβολισμούς έξω από τα γραφεία της οργάνωσης «Χρυσή Αυγή» in.gr 20/11/05 (in Greek)

- ^ «Πεδίο μάχης» το κέντρο της Αθήνας έπειτα από παράλληλες συγκεντρώσεις in.gr 17/09/05 (in Greek)

- ^ a b Article in magazine KLIK(in Greek)

- ^ a b ''Central European Review'' – "Anti-Jewish Attacks". Ce-review.org. Retrieved on 2011-06-27.

- ^ Central Board of Jewish Communities in Greece press release (in Greek). Also contains photographs of the desecrations.

- ^ Greek Helsinki Monitor press release (in Greek)

- ^ trncinfo.com – "Fanatic Hrisi Avgi member released."[dead link]

- ^ "Το παραμύθι του «τρελού» και ο «Χρυσαυγίτης»". Εφημερίδα Ριζοσπάστης. 2001-02-16. Retrieved 2012-04-13.

- ^ Δώρα Αντωνίου, Απόστολος Λακάσας, Νίκος Μπαρδούνιας, Σπύρος Καραλής, Θανάσης Τσιγγάνας (1999-10-23). "Σφαίρες στη συνείδηση της κοινωνίας" (PDF). Εφημερίδα Καθημερινή. p. 3. Retrieved 2012-04-13.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Το δημογραφικό Απαρτχάιντ του 2000". Ιός - Ελευθεροτυπία. 2000-01-02. Retrieved 2012-04-13.

- ^ a b Μουντο-ρατσισμός Eleftherotypia 10/9/2006 (in Greek)

- ^ a b Nazis dressed up as fans, Eleftherotypia 1/12/2001

- ^ Galazia Stratia thanking Chrysi Avgi for the support. Meandros.net. Retrieved on 2011-06-27.

- ^ a b c d 17/04/2004 article in Ta Nea (in Greek) [dead link]

- ^ In Brief Kathimerini. 14/09/2005

- ^ Ο «Περίανδρος» άδειασε την ΕΛ.ΑΣ. Eleftherotypia 14/09/2005 (in Greek)

- ^ 27/04/2004 article in Kathimerini (in Greek) [dead link]

- ^ Παραδόθηκε ο «Xρυσαυγίτης» Kathimerini 14/09/2005 (in Greek)

- ^ a b Αμετανόητη Αυγή του φιδιού Eleftherotypia 29/09/06 (in Greek)

- ^ Είκοσι ένα χρόνια κάθειρξη χωρίς αναστολή στον «Περίανδρο» για την επίθεση κατά φοιτητών in.gr 25/09/06 (in Greek)

- ^ Athens Indymedia 2008/02/03

- ^ ΔΕΣΜΟΙ ΑΙΜΑΤΟΣ Eleftherotypia 2008/02/04 (In Greek)

- ^ Neo-Nazi offices in Greece bombed IOL, March 19th, 2010, retrieved March 27, 2010

- ^ Athens News Agency: Press Review in Greek, 98-06-29. Hri.org (1998-06-29). Retrieved on 2011-06-27.

- ^ a b Eleftherotypia's article part 3 (in Greek)

- ^ Eleftherotypia article part 1 (in Greek)

- ^ Image from the article of Ta Nea

- ^ Indymedia Athens. Athens.indymedia.org (2005-01-22). Retrieved on 2011-06-27.

- ^ Bulgarian Indymedia[dead link]

- ^ "Nikos Michaloliakos: fake document of KYP". Court of first instance, of Athens 52803/04.

- ^ http://www.iospress.gr/mikro2000/mikro20000415.htm

- ^ a b "A guide to Greece's political parties". Al Jazeera. 1 May 2012. Retrieved 5/11/2012.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Explosion at Greek neo-Nazi office, CNN, 19 March 2010, retrieved 2 February 2012

- Porat, Dina; Stauber, Roni (2002), Antisemitism Worldwide 2000/1, University of Nebraska Press, p. 123

- "Greek Voters Punish 2 Main Parties for Economic Collapse", The New York Times, 6 May 2012

- Smith (16 December 2011), "Rise of the Greek far right raises fears of further turmoil", The Guardian

{{citation}}: Text "Helena" ignored (help)

- ^ Freedom in the World 2006: The Annual Survey of Political Rights & Civil Liberties. Freedom in the World. Rowman & Littlefield. 2006. p. 284. ISBN 0742558037, 9780742558038.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Lowen, Mark (30 April 2012). "Greece's far right hopes for new dawn". BBC. Retrieved 5/11/2012.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help)